‘OH beautiful, for heroes proved, in liberating strife…’ That was the line he was anticipating, the next step in a process, the peaceful prologue to 35 minutes and 58 seconds of violence. Yet Lou Duva, waiting to hear the words, appeared as though he wanted to punch someone in the face. Cheeks red, eyes crazed, he raged at all in the vicinity, pointed accusatory fingers and made his sizeable presence known. He was angry, all right. Not as angry as he’d later become but angrier than usual (and Lou Duva was the type of man who projected anger even when content). In that moment, on that night, March 17, 1990, Lou Duva was angry because Meldrick Taylor, his unbeaten world champion and 1984 Olympic gold medallist, was about to make his walk to the ring at the Hilton Hotel, Las Vegas in silence.

“Where’s the music, goddamnit?!” Duva yelled. “Where’s the music?!”

It was at this point he slammed the brakes on Taylor.

“Put the music on or we’re not going in! Put the music on!” As they stalled on the runway, Duva turned to face Taylor, adjusted his robe, and the music began to play. Drum. Horn. Keys. Only then did they move. “Let’s go.”

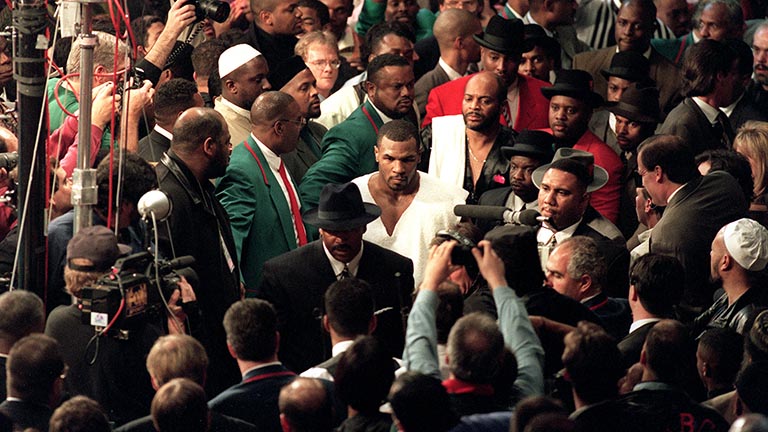

Face buried in a hood, Taylor placed both gloves on Duva’s shoulders and proceeded to lightly jog on the spot as those around him performed a pensive conga and gradually, in unison, made their way to the ring. Evander Holyfield was up front holding the flag of the United States of America, while Pernell Whitaker was beside Taylor feeding him motivation. All were Olympic team mates. Befitting the scene, the song which now played was America the Beautiful, by Ray Charles.

“You know what I find interesting?” said Sugar Ray Leonard during television commentary that night. “Normally you walk to the ring and your song is always upbeat. This song by Ray Charles is very, very slow. It’s interesting.”

Clearly, regardless of tempo, the tune and its sentiment was of great importance to Duva and his posse of ‘84 Olympians. It meant something. It meant more on that day than on any other day, in fact. A song of hope. A song of togetherness. U-S-A, U-S-A, U-S-A. It also, in retrospect, poignantly pre-empted what was to follow; for them, the patriotic Americans, a tragedy of sorts; so near and yet so far; Taylor, ahead on the judges’ scorecards, stopped by Julio César Chávez, the Mexican legend, with just two seconds of their super-lightweight title fight remaining. Alas, to watch the ring walk now is to listen to a sad song made sadder. No longer just a ring walk, the scene resembles an organ-led funeral procession, the march long and sombre.

Ring walk music hasn’t always been this powerful. If you trace its roots beyond live mariachi bands you’ll actually discover it was first introduced for commercial purposes when Muhammad Ali used the Star Wars theme ahead of his heavyweight title fight with Earnie Shavers in 1977. The movie had just been released in the United States and a burgeoning franchise was about to take over the world. The Force got hold of Ali and Ali was savvy enough to acquiesce. Synergy created, it meant no more than that.

Forty years on and popular music is a crucial part of the boxing show. It is played between rounds – minute-long bursts of hip-hop enliven the crowd during the dullest of prizefights – and also in the final moments before a main event. There are even now unofficial playlists synonymous with The Main Event, particularly in the United Kingdom, where punters, many of whom are sufficiently lubricated by alcohol and consequently in the mood to sing and dance, expect to hear Sweet Caroline and Living Next Door to Alice right before ring walks commence and punches are thrown.

It’s ring walk music, though, which truly enlightens. After all, these are not just random songs which accompany a fighter’s lonely strut to the ring. The song you hear is a song they have purposely chosen and therefore much can be gleaned from the selection process. Some boxers choose a certain track because it has personal resonance and triggers an emotional response. Some have the crowd in mind. They want something uptempo, catchy, a song that intensifies the atmosphere and, in turn, energises them. Some, however, when picking their song, think only of intimidation. They want something hard and heavy. It needs to be menacing. Its impact should linger in the mind of the boxer in the opposite corner. Mike Tyson’s entrance song – better yet, call it a series of sounds – for the Michael Spinks title fight in 1988 probably best exemplifies this approach; that incessant drone, those clanging chains, the claustrophobia, the feeling of impending doom.

In time, boxers are defined by their signature song. Chris Eubank will always be (Simply) The Best, Blue Moon will always recall Ricky Hatton thrillers in Manchester, Thunderstruck harkens back to Arturo “Thunder” Gatti and forewarns mayhem, while Can’t Stop has the opposite effect when heard in the context of a Wladimir Klitschko fight.

There’s also a lineage in some cases, songs which travel through the generations. The song Ain’t No Stoppin Us Now, first associated with Larry Holmes and then David Haye, is one example. People forget Haye, up until 2008, had no fixed theme tune. He experimented with varied results. R. Kelly’s Happy People led him into his first professional loss against Carl Thompson in 2004. James Brown’s The Payback told the story of the night he gained revenge over amateur conquerer Giacobbe Fragomeni in 2006. Haye was even known to occasionally make fight week trips to the BBC Radio 1 studios in order to pick up custom-made works of resident DJ Tim Westwood; sirens, explosions, smashing glass and white boy shout-outs. It showed he cared, I suppose. All he lacked was direction.

Cue Holmes and his 1982 heavyweight title fight with Gerry Cooney. It was one Haye watched countless times in 2008, when cooped up in North Cyprus ahead of his own title fight with Enzo Maccarinelli, and one primarily used as a template. Study the way Holmes dissects Cooney, the taller man, with speed and smarts. Study that jab. Haye plays Holmes, Maccarinelli plays Cooney. That sort of thing. But, in the end, Haye’s big takeaway was Holmes’ ring walk song. So upbeat, so full of fun and positivity, Ain’t No Stoppin Us Now by McFadden & Whitehead was a late-70s disco classic, a staple of Haye family parties, but never had the cruiserweight champion contemplated using it as his own ring entrance music. Until then, that is. “It’s celebratory and uplifting and gets the crowd on their feet,” he said. “I’m a big believer in being relaxed and calm on the way to the ring and that song puts me in that kind of mood. I don’t want to be pumped up and angry until I’m in that ring. Before that, it’s a celebration. I want to enjoy it.”

On March 4, 2017, nine years after the Maccarinelli win, Haye’s opponent, then WBC cruiserweight titleholder Tony Bellew, would enter the ring to the strains of Theme from Z Cars, the walk-out music of his beloved Everton Football Club. In doing so he will once again unite a city split by football allegiances. “It’s the only song in the world that makes the hairs on the back of my neck stand up,” said Bellew, who has used Z Cars for all but his first two professional fights. “It’s iconic. It’s emotive. When I hear that song, when I hear that drum roll, I know it’s time to work. Even when I watch Everton games, it has the same impact. There’s something magical about it. It means no more messing, no more talking, it’s time to get down to business. It’s time to fight.

“The Everton fans obviously love it, but Liverpool fans enjoy it as well. There’s something between Scousers. Although we have this big football rivalry, when I hear David Price coming to the ring to (Liverpool Football Club anthem) You’ll Never Walk Alone, I think of Scousers never walking alone. We stand together regardless of the football team we support.”

When Carl Froch was asked to pick not one but two ring entrance songs to be played ahead of his 2014 rematch with George Groves at Wembley Stadium, he experienced a momentary brain freeze. There was no obvious answer. Perhaps it wasn’t deemed significant at that point in time, not with a bitter grudge match set to take place before a crowd of 80,000 people fast approaching. Or maybe he didn’t care.

Groves, his fierce rival, had already settled on his: Kasabian’s Underdog followed by The Prodigy’s Spitfire. The latter had become something of a personal anthem, whereas the former was picked solely for story-telling purposes. It summarised his driven, determined mentality. “There’s a part in Spitfire where it kind of trickles in and then drops and the drop is really nice,” Groves explained to me in 2013 when reviewing the first Froch fight on television. “It gets everyone lively and up for it, whether they like me or not. But they (those responsible for the running of the event) started the song straight from the drop, so you didn’t even notice it had happened. That annoyed me. It made me even more determined to go out there and do a job on him.”

It’s the little things which irk fighters. And little things to us, like ring walk music, like the ring walk itself, mean everything to them. It’s all Groves thinks about when on his way to the ring, he tells me. How does the ring walk look? How does the song sound? Are the crowd enjoying themselves? The rest of it, the opponent, the fight, the pressure, somehow fades into insignificance there and then.

That said, Froch, the champion, was far less concerned with Wembley ring walks. Two songs? You’re having a laugh. But they were serious. Suggestions had to be thrown his way. Rock songs, dance tracks and everything in between. Any take your fancy, Carl? No, not really, he’d say. You pick for me.

Tellingly, it wasn’t until one option plucked from AC/DC’s extensive catalogue referenced being on a highway to hell that he all of a sudden seemed to care. “No, that gives the wrong message,” Froch told members of his promotional team. “It sounds like I’m on my way to hell.”

He settled instead for another AC/DC song, Shoot to Thrill, proving that even in the minds of those for whom ring walk music is an inconvenience, it still matters.

‘I’m gonna take you down – down, down, down. So don’t you fool around.

‘I’m gonna pull it, pull it, pull the trigger.’

Yeah, that’ll do.