By Elliot Worsell

SUCH is the obsession with accumulating in boxing, whether that’s rounds, or belts, or wealth, there remains a belief that comfort can be found in numbers and that to be surrounded by people is a sign not of weakness but in fact strength.

Apparently, the more people you have telling you how strong you are, the stronger you feel. The more people you have looking at you and following you, the more you feel as though you have made it.

Yet surely this, as an idea, flies in the face of what it means to be truly strong and successful, does it not? If, for example, a boxer does indeed require the presence of other men in order to feel at the peak of their powers, what does that really say for their strength? Moreover, if success can only be measured by the amount of people jostling to exploit a boxer’s ignorance, what does that say for the true meaning of success?

The truth is, there has always been a correlation between the success of a boxer and the number of people surrounding them. Win fights, get noticed, and soon they arrive, like cars slowing down at the scene of an accident. Similarly, there has always been a correlation between the rise in the number of people surrounding a boxer and the reduction of collective knowledge in the room; gym or elsewhere.

These thoughts returned to me recently when a couple of boxers mentioned entourages and how their success of late owed to a concerted effort to keep theirs small – non-existent really. Both, too, were speaking from that most valuable position: experience.

“I learned a few dos and don’ts on fight week,” said Frazer Clarke, a British heavyweight who was reflecting on the time he worked security at the start of his boxing career. “As you see, I don’t come with a big crowd of people. I don’t want a big entourage. I’m quite low maintenance. I’m not a superstar and don’t try to act like one.”

Frazer Clarke (James Chance/Getty Images)

Likewise, Andy Lee, a former world middleweight champion who has in retirement become quite the coach, has attributed the uptick in form of Joseph Parker, his heavyweight, to a stripped-back approach.

“Compared to camps I’ve been in with other fighters, where there has been 15 people hanging around and everyone has a say or an opinion, and they’re quite strong personalities, this is completely different,” Lee said. “In our camp it’s just me, Joe (Parker) and George (Lockhart; Parker’s strength and conditioning coach). Everyone else is just happy to be there – if they are there.”

For a coach there is presumably no nicer feeling than space and no better sound than silence. In this environment, after all, there is ample room in which to learn and far less chance of the stock platitudes and hollow praise of others becoming the single thing driving the boxer. In this environment, you tend to find the only ingredients a boxer really needs: gloves, a dream, and a coach.

Rarely, however, is boxing ever this simple or pure. In fact, often what happens when a boxer becomes successful is that their gym is quickly polluted with people more than happy to give the boxer whatever it is they want to see or hear, bullshit fed to them on a drip. This can be related to boxing, which is the stuff really hard to swallow, or it can be related to outside pursuits, business propositions and future plans, all of which have a way of catching the boxer’s ear and highlighting their inability to discern the difference between snakes and ladders. Typically, too, these people will be working for free and will be remunerated only in the feeling of belonging and being accepted, or in the form of ringside tickets. For some, this is enough; enough to keep them coming back; enough to ensure they say what the boxer wants to hear; enough for them to live vicariously through another man.

That’s why gyms of successful boxers tend to be full of people standing around wasting time watching one man go about their work, invariably topless. In the process, these men will make small talk with each other, creating tiny communities centred on the same niche interest (a specific boxer), and they will wait for the boxer to say something funny or do something physical, knowing their job then is to either clap their hands (if doing something physical) or laugh uncontrollably (if saying something funny). They are, in that sense, the great narrators of a boxer’s life, becoming, along the way, a voyeur who sees everything yet knows absolutely nothing about what it is they are seeing.

It is a strange phenomenon really, boxing’s tribalism. It becomes stranger, too, when you see a gaggle of geese follow a boxer into a press conference and occupy all the seats designated for press in order to essentially gaze in wonder and listen to the boxer’s every word as though in these words they will find the meaning of life; theirs, or more generally speaking. Followers in every sense, they will at this time usually be wearing clothes emblazoned with the boxer’s name, or their logo, and they will consider this their uniform, proof of their inclusion.

“I remember back in the Detroit days fighting on a Sergio Martinez undercard and he’d have a big entourage,” said Lee. “All of them would have Sergio Martinez tracksuits on with ‘Team Maravilla’ on the back. There was something in that, I thought. A strength. It wasn’t intimidating, but it lets your opponent know.

“There’s good and bad to having an entourage, I suppose. If it’s done right, it can be powerful. When Joe fights, his entourage will arrive – his brother, his cousins, his friends, David Higgins (Parker’s manager) – and there will probably be 15 people with him all wearing the same tracksuits. So, when we go to the press conference, all the opponent is seeing is Joseph Parker tracksuits everywhere. When we then go to the weigh-in, we’re all together in uniform. There’s strength in those numbers and Joe probably feels insulated. There’s a sense of protection for him in terms of there being a barrier between him and journalists or the public or other fighters. The opponent feels it, too. They think, Look how many people he’s got here. It does mean something and there is strength in it. But it has to be done right and it very easily goes wrong.”

Andy Lee (James Chance/Getty Images)

Last year, while in Las Vegas covering the welterweight title fight between Terence Crawford and Errol Spence, I saw, at the pre-fight press conference, a press section overrun and dominated primarily by the two fighters’ entourages. There was, for some of the press, nowhere to sit as a result and, worse, soon it became all about them, the entourages, rather than the boxers on stage.

“You’ve got to calm down, brother,” Crawford said, addressing Spence’s cousin, who had thought it wise to start heckling him from press row. “Listen, man. Things can get sticky real quick and then everybody will be saying this is what we do every time we come out. Just like you’re talking, it can turn deadly real quick – on both sides. Why not support your fighter and let’s come together and make this event a success instead of everybody saying that when we come together this is what happens? That’s what I want.”

Errol Spence and Terence Crawford (Getty Images)

Naturally, this exchange left everybody on edge; grateful for the metal detectors through which we had earlier passed when entering the T-Mobile Arena. It also shone a light on boxing’s desperation for attention and how, even at a press conference, we have allowed stories to be told by just about anyone to stoke the drama and create a viral moment for those standing around filming everything on cameras or phones. In that respect, one could argue that never has the job of sycophant been more important and potentially lucrative than today. After all, now, thanks in large part to social media, there is a chance these attention-seekers will be seen following a boxer and become online famous off the back of it. If in doubt, look around. It’s happening everywhere. Stick with it long enough and you may even get a job.

And yet, despite its apparent upside, it is a mostly one-sided, transactional relationship, this relationship between boxer and hanger-on. It is warped from the very beginning, predicated on a one-way interest between two people that only seems peculiar when you try to reframe it; picture, for instance, a boxer showing up at a man’s office job every day of the week to sit near him at his desk and do no more than watch him go about his work. In that scenario, the behaviour of the boxer would be deemed unhinged, if not a little creepy. However, transpose the office for a boxing gym and all of a sudden the behaviour is deemed normal; normal, that is, until one day the boxer retires and there is both a sizeable void and a shared realisation. For the boxer, they soon come to realise the people around them, for the most part, cared only about them as The Boxer and what success in this role could do for them. This leads then to an identity crisis in retirement and an acceptance, for some easier than others, that not everyone in the real world is being followed by a team of people showing an unhealthy level of interest in their every move.

For the hanger-on, meanwhile, the realisation is just as stark. With the boxer now retired, they will likely realise once and for all how little the boxer actually knew, or for that matter cared, about them; the form of the fighter forever superseding the life of the observer.

“I’ve been a person who has always kept their team small,” said Michael Conlan. “I have very few close friends around me. I always see so many fucking hangers-on in boxing. Look at someone like (Anthony) Joshua, for instance. I think he has too many hangers-on and too many voices around him. I’m not a fan of Ben Davison (Joshua’s coach) as a person, but, as a coach, I think he has done a great job with Joshua and he’ll continue doing a great job with him. He seems to have got into his head as a single voice and Joshua appears to trust him. That’s a good thing.”

When turning pro in 2017, Conlan, a star amateur from Ireland, was walked to a ring inside Madison Square Garden by one Conor McGregor and appeared destined to find himself surrounded at every turn. Yet, in fairness to Conlan, that was never the path he took. Instead, upon turning pro he deliberately removed himself from the comforts of home and has throughout his career been something of a fighting vagabond, living for weeks on end wherever his gym happened to be located. That could mean Coulsdon, Croydon. Or it could mean Miami, Florida. Wherever it was, Conlan would be seen surrounded only by men who either think like him or look like him.

“I have my brother and we look at life from a brother’s perspective first (Jamie Conlan also manages Michael),” he said. “When I spar, the only person I send footage to is my brother. His opinion is one of the ones that matters to me. I just like things straight and honest. If you’re that way with me, I’ll be that way with you. Even if you’re not straight and honest with me, if I don’t like something, you’ll know. If I like you, you’ll know, and if I don’t, you’ll also know. I find it very hard putting on false faces.

“These people around boxers don’t have a clue. Too many of them are just fanboys, and I include the coaches in that. Some coaches will just say to their fighter, ‘Yeah, it’s amazing,’ and not spot the things they should be spotting; or, if they do spot them, they are too scared to point them out.”

Michael Conlan on his way to the ring (Getty Images)

“The head coach has to be the captain of the ship,” said Andy Lee in agreement. “He decides everything; when it’s done and how it’s done. That’s when everything runs well. Those decisions shouldn’t be on the fighter. He should be focused on fighting and making weight, if that’s the case. That’s how it is with Joe. He directs everything to me and I deal with it. But when you have entourages and they’re not in sync, and you have a variety of people doing stuff that conflicts with the boxing, it’s not good.

“I’ve been in some camps where there are too many people involved and every person has their opinion. If the coach is not a strong personality, or on top of everything, those voices can grow and easily turn a fighter’s head.”

Lee himself, while a popular fighter who made friends wherever he went, was never inclined to have much of an entourage during his own career. “All service is self-service,” he said. “I used to always think that when someone did something for me.” Equally, Lee was able to see how others fell for the lure of being surrounded by a chorus line content to continuously hum their favourite song. “Whatever insecurities you have, if someone’s making you feel good about yourself, you’ll take it. If the coach is saying you’re looking like shit in the gym, you might look for the words of someone else to restore your confidence. That stuff is very common for a coach to say, by the way. Sometimes you might need to hear it. But if there’s also someone saying, ‘Man, you’re looking great,’ who are you going to listen to? You already feel insecure and bad about yourself.”

The likes of Lee and Conlan, two men whose wisdom and humility were beaten into them by their first love, speak now from experience and with the benefit of both distance and hindsight.

For the younger fighters, though, fighters like Xander Zayas, a Puerto Rican of whom big things are expected, cautionary tales may sound like urban myths. Which is perhaps why Conlan, when hearing I was set to interview Zayas about his next fight, was adamant I should include the 21-year-old prospect in our conversation about entourages.

“I was around him in the Top Rank days and he’s a lovely kid,” he said. “Top Rank are building him massively and maybe building him too fast. He’s only young. He has time. But they want him to be the next fucking Miguel Cotto without, in my opinion, the substance behind it.

“When you have the backing of an entire country, you just need to know what is real and what is not in terms of the hype. You have to match the hype with the substance.

“I think he will probably be a bit blinded (to the dangers of an entourage), but you should ask him the question because then it at least puts it into his head that he needs to be smart about it. You’re the only person who will ask these types of questions. People don’t ask these questions about entourages and stuff, so boxers aren’t even aware of what is happening to them. Stuff like this needs to be said and questions like this need to be asked. There are so many fucking snakes in boxing, people only in it for their self-benefit, and the fighters don’t realise this until it is too late.”

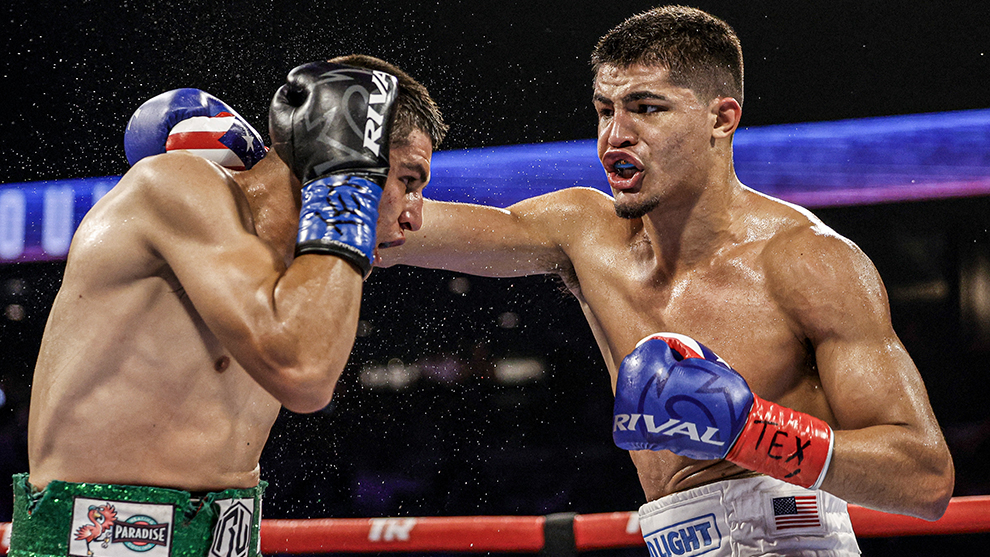

Xander Zayas attacks Roberto Valenzuela Jr. during their fight at American Bank Center on September 15, 2023 in Corpus Christi, Texas (Carmen Mandato/Getty Images)

So, on Thursday, I asked him. I asked Xander Zayas how he controlled the hype and the voices in his ear and I asked him how he limited the number of people allowed to get close to him.

“My close circle knows that when I’m in camp, we’re not going out, we’re not watching any movies, we’re not going to get food; we’re not doing anything. I’m in camp,” Zayas said. “That means I’m going from the gym to the house and from the house to the gym. That’s it.

“Secondly, you’ll never see me with somebody different. You’ll see me with the same people every time out. I don’t like bringing in new people. Sometimes, if my friends are going somewhere, I’ll just stay home. I wouldn’t say I’m anti-social, but I just don’t like it when they try to bring new people into my circle.”

At 18-0 (12), Zayas, a super-welterweight, talks well and with refreshing maturity. Yet, of course, the conviction with which he currently speaks stems as much from inexperience and ignorance as simply maturity. For, after all, like most things in life, whether it’s love or loss, handling fame is not something for which you can adequately plan or prepare. Nor can a boxer like Xander Zayas ever expect to know or appreciate its impact until he is one day telling some other 21-year-old about the dangers of letting too many people in.

“I don’t think it will be hard,” he said when, on Conlan’s behalf, I asked him if he was aware of what was to come. “I’ll just say no.”