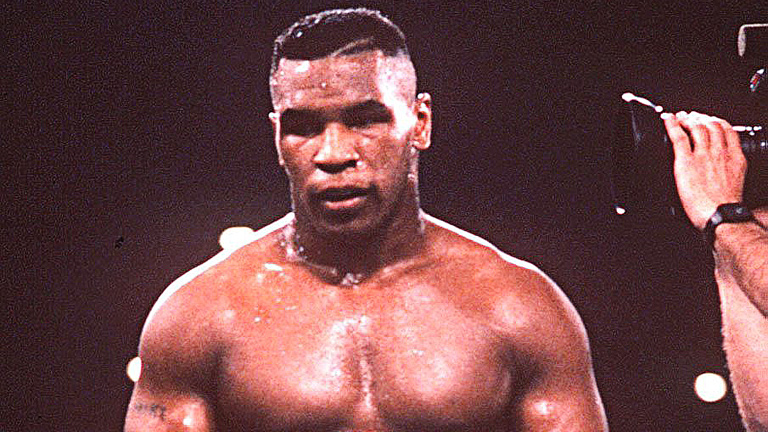

Mike Tyson and the ghosts of boxing’s past

Springs Toledo, with a little help from Mike Tyson himself, investigates the myths and legends, the eerie parallels and undeniable truths, that shaped the life of the former heavyweight king. From fatherless beginnings to humble endings, Toledo argues that the eternal underachiever actually accomplished far more than he ever should

HE’D be upstairs in the dark, pitched forward in a chair, watching ghosts. His face, broadening in adolescence, flickered in light as the projector clicked and hummed. He watched fight films — “all night long,” he said years later. “I’d crank up the volume and the sound would travel through the old house.”

The old house was the headquarters of an old man named Constantine (“Cus”) D’Amato — an eccentric genius of fistiana who had made a lot of enemies 20 years earlier, when he managed heavyweight champion Floyd Patterson, when he was relevant. The 14-year-old upstairs grew up in desperate circumstances in the Brownsville section of Brooklyn, his father long gone, his mother a barely functional alcoholic who slept with strangers to provide short-lived shelter for her children. There were nights, winter nights, when he was huddled with her and his siblings in abandoned buildings. He was a target for bullies, a misfit with a lisp and bad hygiene who felt most at home on roofs with pigeons. When he was seven he stopped going to school after someone tried to steal his meatballs and dropped his glasses into the gas tank of a truck. Before reaching puberty, he was breaking into people’s homes and blindsiding old ladies to take what little they had.

He was a study in despair masked by anger. The Tryon School for Boys in upstate New York was his last address before a Youth Division Aide and ex-fighter named Bobby Stewart brought him to the old house in the Catskills and introduced him to D’Amato. Tyson became one of many troubled boys under the old man’s wing, but there was something in him, malformed though it was by years of abuse and neglect. D’Amato knew it immediately. The boy didn’t and the man still doesn’t. “I was this useless thorazined-out n***a who was diagnosed as retarded,” Tyson said, “and this old white guy gets ahold of me and gives me an ego.”

D’Amato gave him more than that.

Dr. Viktor E. Frankl addressed despair not with probing questions from a chair to a couch but with a call to action. He understood that life is not the preoccupation with pleasure Freud figured it was but a struggle for meaning; that behind feelings of futility and emptiness is a warning sign easily overlooked — boredom. “Life is a task,” he said. The existential question that asks “what is the meaning of life?” becomes “what is the meaning of your life?” and active listening becomes exhortation: “Learn what you should be from what you are.” Direct your thoughts to climb over your circumstances, identify your mission. See it large. See yourself larger.

I have a feeling that Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning was on D’Amato’s bookshelf. “Listen,” he said to the dead-end kid that was Tyson. “You can be something very special. You can be champion of the world. You can devastate the world. You just gotta believe it.” Teddy Atlas was nearby and knew what it meant. “This was a road out,” he said, “a real way to alter the course of his life.”

“In 200 years,” Donald R. Cressey said, “we have done nothing to prevent crime by nonpunitive – positive reinforcement – methods.” Cressey, who spent decades studying the causes and prevention of crime and delinquency, was interviewed by John H. Laub in Criminology in the Making: An Oral History. In 1993 and again in 2003, Laub and Robert Sampson presented a new theory rooted as much in common sense as it is in rigorous methodology. “Life course” theory identifies dysfunctional families and school failure as strong predictors of delinquency, and holds that persistent offenders lack these and other relationships that provide emotional support and restrain anti-social impulses. They also found what Cressey was looking for — a road out, a break in the cycle. The risk factors of growing up with severe disadvantages (and Tyson had all of them) may be overcome by “turning points” that pivot life trajectories away from criminality and likely incarceration.

Tyson’s psyche was being recalibrated in a boxing gym upstairs from the Catskill police station when he found out his mother died. He was 16. D’Amato, who shared the house with his companion Camille Ewald, immediately began the process of legally adopting him. Tyson, his despair unmasked, approached Ewald and asked if it would be all right if he called her mother. “So from that time,” she said, “I became his mother, Cus became his father.”

There is no miracle to relate here, however. Even after winning a number of amateur titles, Tyson continued making his way back to Brownsville and went on a crime spree and drug binge after his mother died. Criminologists see this as not atypical. Desistance from crime, Laub and Sampson assert, is understood to be a process, and the process can be fitful when too many childhood risk factors are in play. Still, Tyson’s adolescence bucked expectations. After he became immersed in the strict regimen of the hardest sport – early morning roadwork, constant drills, isometrics, sparring sessions – he had little time left for street crime. At the age when his criminal offending would be expected to peak, it declined. “I started believing in this old man,” Tyson said. “Then I stopped doing all that. I changed my whole life.”

To call it a moral conversion would be an overstatement, but something remarkable happened. He transitioned away from one pattern of behaviours and toward another in a process made easier by the kinship boxing has with street values: Courage in the face of adversity, skill and strategy, strength and power. These are mythologised in the ring and have been idealised in high-crime urban areas since at least the days of ancient Rome.

“We have known for a long time that crime, especially violent crime, is concentrated by place,” Laub said. What is less discussed and no less true, is that those areas where violent crime is concentrated are also where fathers and male role models are not. “It is troubling,” Laub and Sampson assert, “that many sociological explanations of crime ignore the family.” It is more troubling that fatherlessness specifically has been virtually ignored in the social sciences despite its links to a host of pathologies from delinquency and depression to substance abuse, suicidal ideation, and school shootings. The destructive consequences of fatherlessness are particularly acute for boys. Needless to say, the benefits of a strong male role model in the home are immeasurable, as a buffer against every criminogenic variable, as a bulwark against despair.

Tyson had none during his formative years, then he had one, then many.

When D’Amato first began pulling him out of Brownsville, he tossed him a Bible-sized book about the great fighters of boxing’s past. He read it from cover to cover and discussed what he learned for hours on end with D’Amato, who knew many of the personalities on the pages. They shared Tyson’s background; some emerged from worse. “I never looked at myself as in their league,” he says, but he was driven to become “a part of their fraternity.” With D’Amato at his side, he was going to fight his way into not only their fraternity, but into the historical succession of heavyweight kings, a succession that stretches back into the 19th century.

The Bible-sized book, the long discussions, and the access Tyson was given to a library of fight films all had a clear purpose. D’Amato, well into his seventies, sought to accelerate Tyson’s development before mortality beckoned. There seems to have been another, more mercurial purpose. D’Amato was proud and paranoid, perhaps too proud and too paranoid to completely entrust his legacy to anyone — at least anyone alive.

After four years fighting as an amateur and winning damn near every tournament he was brought to, Tyson was turned professional in 1985. He was put on a gruelling schedule that old-time fighters would have applauded.

“I wanted to be like Harry Greb,” he told me.

“Harry Greb?” I said. “He went 45-0 in 1919.

“And he fought in three divisions. Those guys lived to fight back then. I wanted to be like them.”

Tyson fought 15 times in his first 10 months as a professional, which was better than Greb. He was 11 fights in when D’Amato died in November 1985.

Only days after the funeral, Tyson stopped Eddie Richardson in Houston and his gestures before and after the carnage confirmed that he was not alone, that he hadn’t been left unattended: When introduced, he extended his gloves in front of him, palms up, which is what Jack Dempsey used to do. After a left hook sent Richardson flying sideways across the ring, Tyson went over and helped him up, like Dempsey used to do. I asked him if that was who he had in mind. “Definitely. Isn’t that crazy?” he said. I told him I don’t see it that way. He was paying tribute to his predecessors on the world stage; “you made history come alive.”

At six-feet-six, Richardson was nearly as tall as Jess Willard, the giant Dempsey toppled to take the heavyweight crown. He was only the first of almost a dozen opponents Tyson would stand literally eyes to chest with. Would it be accurate to say that D’Amato designed him to devastate those towering boxers who had taken over the division? “That’s very accurate,” he laughed.

Tyson’s march to the heavyweight throne was not unlike Joe Louis’ 50 years earlier. Louis cleared the field of former champions Primo Carnera, Max Baer, and Jack Sharkey on his way to challenge then-reigning champion James J. Braddock. Tyson’s era was more confused, though he did the sport a favour by clearing a host of claimants and former claimants before facing Larry Holmes, a man D’Amato demanded he defeat.

Tyson-Holmes was loaded with historical significance. Tyson sought to make good on a promise to avenge Muhammad Ali, whom Holmes had stopped eight years earlier, much like Roberto Duran avenged Ismael Laguna by stopping Ken Buchanan and Sugar Ray Robinson avenged Henry Armstrong against Fritzie Zivic. Ali himself was a witness at ringside when Tyson knocked Holmes down twice in the fourth round. He watched Tyson barrel in as his old foe threw a last desperate uppercut that got caught on the ropes. Holmes recalled a moment of wide-eyed panic when that happened – “I said ‘oh shit’!” Tyson landed a right and Holmes was down on his back when the referee waved the fight off. In the camera-jostling chaos that followed, as handlers and officials streamed through the ropes, Tyson strolled over to centre ring and faced the fallen with his gloves on his hips, hero-style.

It was an intentional pose. “Battling Nelson used to do that,” he said when I pointed it out. “He did it before anyone.” It made me think of another one of his predecessors, namely Jack Johnson. Tyson knows all about Johnson. In 2014, he started a petition to persuade President Obama to posthumously pardon Johnson, who was convicted under the Mann Act in 1913 for transporting his white girlfriend across state lines for “immoral purposes.” “The unjust prosecution ultimately tarnished Jack Johnson’s legacy,” Tyson argued, in vain it turned out. I got him talking about the struggles of history’s first black heavyweight champion.

“Can you imagine fighting in front of all those people who want to see you dead?” he said. “Jack Johnson was told that if he won, he’d be killed, and he won anyway.”

“He was surrounded by lynch mobs – sixteen thousand heads deep at Reno – and he was laughing while he fought,” I said.

“Yeah, and he was all alone. Him against the world.”

When I told him that Jack London’s plea that former champ Jim Jeffries come out of retirement and “wipe that golden smile off Johnson’s face” made me want to throw out my copy of The Call of the Wild, he checked me.

“Nah, don’t do that,” he said. “No one’s perfect and you can’t deny he was a great writer. I loved White Fang.”

I don’t love those White Hopes he set on the march. Jim Jeffries was the first and Johnson smashed him to the canvas just like Tyson did Holmes 78 years later. In fact, Johnson can be seen on the film standing over the fallen with his gloves on his hips, hero-style. A framed photograph of the fight hangs over Tyson’s couch at home.

The Holmes fight stands as a culmination of all those nights Tyson studied films in D’Amato’s attic room. “Watching him fight so many times,” he said during the post-fight interview, “I was expecting everything he done tonight.” Somewhere, D’Amato was laughing.

Tyson-Holmes was billed as a championship bout because by then the sport was routinely raising the middle finger to its own history. It was no more a championship bout than was Joe Louis’ destruction of former champ Max Baer, also in four rounds. Tyson, so the fiction goes, defeated Trevor Berbick in 1986 at age 20 to become “the youngest heavyweight champion” on record. That record is revisionist. The fact is, Tyson was a contender rated by The Ring at No.7 to Berbick’s No.1 going into that fight and was handed Berbick’s bogus WBC belt coming out of it. Tyson did not join the true historical succession until June 27, 1988 when he knocked out Michael Spinks. He was three days shy of 22, which makes him younger than Ali and older than Floyd Patterson.

Tyson’s fairytale narrative combined with the fact that he was a cultural icon at 20 has resulted in collective myopia. Boxing pundits tend to take his accomplishments for granted, as if they were inevitable, and fail to recognise Tyson for what he is — an historical anomaly.

Before him, a heavyweight under six feet tall had not dominated the division since Rocky Marciano. Marciano fought in the 1950s, when heavyweight contenders were about two inches shorter and 25 pounds lighter than they were in 1988. Tyson knocked out six fighters who stood at least six-five, which is more than Marciano and Joe Frazier combined ever faced. Tyson’s speed was no less atypical. Juggernauts with bulky arms and thighs should not be able to change their angle of attack so suddenly or fire blinding combinations. D’Amato built a heavyweight Henry Armstrong — a rigorously disciplined, hyper-aggressive champion renowned for overwhelming giants.

“Is that who your style was patterned after? Armstrong?”

His answer surprised me. “Duran,” he said. “The counters, the head movement, aggression.”

Armstrong and Roberto Duran were routinely physically overmatched only after they invaded higher weight divisions. Tyson, by contrast, was outweighed by at least 10 pounds in 36 per cent of his fights and was the shorter man in 90 per cent.

“Even Marciano had a half-inch on you,” I said. “I don’t see it ever happening again—a fighter under six feet dominating the heavyweight division.”

“You never know,” he said. “Maybe someone special will come along.”

“Were you special?”

“I wanted to be the best.”

“I’d say you were, and everyone knew it when you stopped Holmes and Spinks.”

But by then D’Amato was dead and the discipline was dying. “I’m a professional and I don’t get involved emotionally because it inhibits my performance,” he said in 1986. That was before he signed a promotional contract with an electrified pimp and married a gorgon. By the end of 1988, manager Jim Jacobs had died of leukemia, trainer Kevin Rooney was shown the door, and Tyson was street fighting, giving away Bentleys, and turned upside down by a wife who had one leg and a mother-in-law who had the other.

“The only safe place for Mike Tyson,” said Larry Merchant in early 1989, “is in the ring.” Rooney told Merchant that “Mike won’t forget everything that Cus taught him and what I’ve been helping to keep teaching.”

Buster Douglas soon proved he’d forgotten enough.

Three years in prison for a rape conviction sapped his body and his spirit, and by the time he faced Evander Holyfield his style had devolved. He was fighting like a brute and was increasingly prone to mayhem in the ring—biting ears, trying to break arms, shoving aside referees.

“I don’t believe I was as good as I could’ve been,” he says now. I told him he was better than he should’ve been.

The more you look the more you see. Tyson’s prime was fated to end early because even if he had maintained his discipline, even if Rooney never left, nature was never going to allow him to retain such speed and explosiveness for long. A brief prime is the red pill of Tyson’s fighting style and that’s to be expected of any style so reliant on fast-twitch fibers and constant aggression.

What is most remarkable about Tyson’s physical decline, then, is not how sudden it was but how subsidiary it seemed to be. For 16 years, he was either rated in the top 10 or at the top of the heap. At 34 he was still capable of knocking out contenders who towered over him and outweighed him by 20 pounds. What was behind this staying power?

Boxing stripped down to its most basic essential is a test of wills. Tyson understood this. As he himself was stripped down both personally and professionally and the powers of youth began to give way, he returned to D’Amato’s attic room. Grainy images of brutal men and brutal fights teemed in his addled mind. A motto, “kill or be killed” fell increasingly from his lips. “I’m Sonny Liston, I’m Jack Dempsey, I’m from their cloth,” he said near the end. It was not off the cuff. Liston used to beat up cops. Dempsey’s shadow was cast in hobo jungles and whorehouses.

Tyson had come a long way since Brownsville, but he travelled in a circle. He had gained the kind of material wealth most only dream of, but had lost more important gains. The mood swings and episodic rage were indications that he was regressing, returning to what may have been his natural state of despair. But his role models never left him. They urged him on, no longer to the glory that was gone, but to the destruction that awaited all great champions who linger too long.

In 2002, his rage and memories of rage finally burned out. Fifteen years had passed since he stood over Holmes like Jack Johnson stood over Jeffries, like a hero under the sun. As history would have it, his career was effectively ended the same way Johnson’s was in 1915 — by a giant.

Lennox Lewis had battered him into exhaustion by the end of the seventh round. His eyes were swollen and smeared with blood when he wobbled back to the corner and slumped on the stool. “You got to stop it,” he said. But the instinct to save himself passed as quickly as it had come. When the bell rang he stood up and charged the giant.

“He just continues because of his character,” he said during an interview in 1985. “That’s the way a fighter should end his job. On his back, until he can’t do nothing no more.” D’Amato sat beaming beside him and added something that sounded like a promise. “If his interest allows, and his will and ambition and his dedication is great, he becomes what he wants to become.” He becomes what he wants to become.

At 2-01 of the eighth round, Tyson hurled a last desperate overhand at Lewis’s head. It missed. That’s when Jack Johnson appeared in the ring with him.

Lewis finished Tyson with a crashing blow from a huge right hand, just as Jess Willard finished Johnson in 1915. From there, the details meld together with startling exactness. Tyson and Johnson can be seen on the film crumbling to the canvas as one, in the southeast corner of the screen, where they lay on their back, legs bent. If you look closely enough, you’ll see Tyson, his mind in a fog, instinctively reach his glove up and rest it on his face, like Johnson did, to block the sun.

The historian who is more than an historian is over 50 now. “They’re my heroes. I watched those old fighters all the time,” he told me. “That’s all I did.”

“I think they were watching you too,” I said. “I think there were ghosts in that ring with you.” Greb. Dempsey. Louis. Liston. Battling Nelson. Jack Johnson — especially Jack Johnson.

“I’m glad they were on my side,” he said. And then he went quiet for several seconds. I thought of an 8mm reel whirling backwards and flickering light, a dead-end kid lost in the anger of despair, a hand – many hands – reaching for him, pulling him upwards.

“Mike?”

“Yeah. I’m one of those guys.”

Springs Toledo is the author of Murderers’ Row (Tora, 2017), In the Cheap Seats (Tora, 2016), and The Gods of War (Tora, 2014). All three are available at Amazon and Amazon UK.