YOU wouldn’t think Avery Sparrow had just returned from a year’s layoff as he shadowboxed and hit the pads. Dressed in a black T-shirt and black tights, his jab darted out fast and straight, often in doubles and triples. He looked graceful ducking and moving laterally, first to his left and then to his right, his combinations were a blur.

The 25-year-old Philadelphia lightweight hadn’t wanted to talk about the year he was without a boxing licence, which was understandable under the circumstances. His post-fight urine sample had tested positive for cannabis following his second-round stoppage of Jesus Serrano on March 19, 2018. The victory was changed to no-contest and Sparrow’s fast-rising career came to an abrupt halt.

With his comeback fight with local rival Hank Lundy just a few days away, Sparrow finally agreed to a private interview at a downtown gym where a public workout was taking place. He was understandably guarded at first, but relaxed when informed the article wouldn’t be published until after the fight. He didn’t want to be labeled a “stoner” going in.

Sparrow’s suspension came at a time when public opinion concerning cannabis use in the United States is undergoing a sea change. 10 states and Washington, D.C. have legalised recreational cannabis for adults. According to the Pew Research Center six in 10 Americans support legalisation of marijuana, as compared to 16 per cent in 1990. Medical marijuana is already legal in 33 states.

It is generally accepted that smoking or ingesting cannabis decreases reaction time, disrupts hand-eye coordination and perception and diverts attention. Therefore, it’s the antithesis of a Performance Enhancing Drug (PED). Nonetheless, cannabis remains on the Word Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) and the Unites States Anti-Doping Agency’s (USADA) list of prohibited substances for boxers.

“I feel that if it doesn’t enhance your performance, it shouldn’t be on the banned list,” Sparrow said. “I think the sport needs to catch up with the laws. As time goes on it will evolve, but at this point boxing is a little bit behind.”

California and Nevada, two of boxing’s busiest states, have legal recreational cannabis. Under state law it’s in the same category as tobacco and alcohol, neither of which are on the WADA and USADA’s banned list.

Neither Bob Bennett, Executive Director of the Nevada State Athletic Commission, nor Andy Foster, Executive Director of the California State Athletic Commission, believes cannabis is a PED. Still, even if they wanted to remove it from the prohibited substance list, they couldn’t.

As government employees, it’s their job to enforce the state’s licensing regulations, which uses WADA’s prohibited substance list. In what amounts to bureaucratic chain of command, the United States Anti-Doping Agency (USADA) is a signatory of the World Anti-Doping Code as set by WADA.

Cannabis was legal for many decades in the United States and in the late-19th century it became a popular ingredient in many medicinal products. How it became illegal is a tale of racism, propaganda and politics.

Much like today’s so-called immigration crisis at the U.S.-Mexican border, when Mexicans crossed into the United States following the Revolution of 1910 they were greeted by unfounded prejudices and fears.

“Police officers in Texas claimed that marijuana incited violent crimes, aroused a ‘lust for blood,’ and gave its users ‘superhuman strength.’ Rumors spread that Mexicans were distributing this ‘killer weed’ to unsuspecting American schoolchildren,” wrote Eric Schlosser in The Atlantic magazine. Fake news isn’t a recent invention.

Harry J. Anslinger, a J. Edgar Hoover wannabe, was the founding commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotic and drafted the Marijuana Tax Act of 1937. He also used racist language during his anti-cannabis campaign, such as “Reefer makes darkies think they’re as good as white men.”

The practice of using cannabis as an excuse to suppress certain segments of the population was intensified when President Richard Nixon declared a War on Drugs in 1971. In 1994 John Ehrlichman, Nixon’s counsel and Assistant for Domestic Affairs, revealed drugs and drug abuse wasn’t the target. It was aimed at the anti-war left and blacks.

WADA, located in Montreal, Canada, was founded in 1999, but it wasn’t until 2012 that voters in Colorado and Washington approved ballot initiatives to legalise recreational marijuana. Therefore, cannabis was probably included on WADA’s banned substance list simply because it was illegal, not because it could enhance performance.

Even WADA has made a small concession to the change in public opinion and the modifications of the law. It has raised the cannabis threshold to 150 ng/mL, which means nanograms (one billionth of a gram) per millimeter of blood. The new permissible threshold means that regular smokers would need to stop smoking 28 days before a test, instead of 30.

“It needs to be dropped from WADA and to not do so is unfortunate. All commissions need to stop including it,” said Dr. Margaret Goodman, co-founder, along with Dr. Edwin “Flip” Homansky, of the Voluntary Anti-Doping Association (VADA), which was launched in 2011. “VADA removed cannabinoids in 2012. We do not believe they’re performance enhancing and should not be included on any prohibited list. Changing the threshold for the labs proves organizations agree.”

Due to its state-of-the-art testing procedures, random no-warning testing and independence, VADA is widely recognized as the most reliable anti-doping organization. Many prominent boxers have signed with VADA, including, but not limited to, Deontay Wilder, Gennady Golovkin, Anthony Joshua, Manny Pacquiao, Errol Spence, Oleksandr Usyk, Terence Crawford, Canelo Alvarez, Vasyl Lomachenko, and Nonito Donaire.

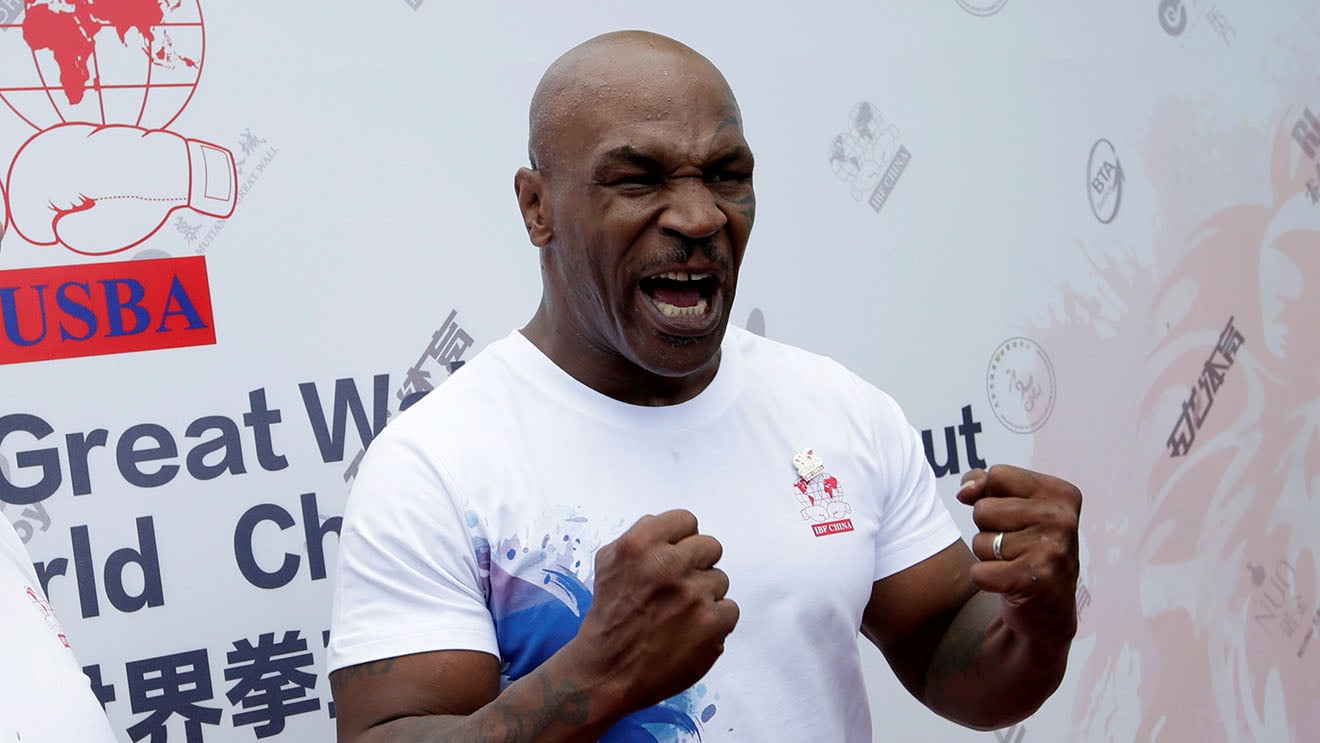

One of boxing’s most prominent cannabis busts came on October 20, 2000, when Mike Tyson tested positive for marijuana after stopping Andrew Golota. The result was changed to no-contest, Tyson was suspended and fined $200,000.

Today, Tyson is a budding (pun intended) cannabis mogul. In partnership with Jay Strommen and Robert Hickman, he’s opened Tyson Ranch, a forty-acre cannabis resort in California City, a town in the Mojave Desert two hours outside of Los Angeles. The ranch also cultivates its own brand of weed.

Tyson readily admits he’s used marijuana most of his life and had smoked before the Golota fight, but insisted it was the only time he fought high. He also credits cannabis with helping him come to terms with himself after leading a tumultuous existence for most of his life.

“I like who I am when I smoke. You know what I mean?” Tyson said during a January 2019 appearance on the Joe Rogan Experience podcast. “Without weed I don’t like who I am sometimes … it makes me nicer. It calms me down.”

Of course, a mellow mood is not the mindset most boxers would want when the opening bell rings. It’s a fight, not a love fest. Not even Tyson would recommend smoking a joint in the dressing room.

“If you smoke a joint right before the fight, that’s wrong because it could effect your performance and you could be injured,” said Hall of Fame promoter Bob Arum, a longtime user and cannabis advocate. “But if you smoke a joint a month before the fight who care, and whose business is it?”

Arum has got a point. The psychoactive effects of cannabis can last up to two days, but that’s rare. Nonetheless, traces of it can be found in your body a month or more after use.

According to Verywell, a website designed to provide information to health professional, “some of the THC metabolites (the principle psychoactive elements) are stored in fat and have an eliminations half-life of 10 to 13 day. It takes five to six half-lives for a substance to be almost entirely eliminated.”

There’s no way to prove or disprove it, but most likely the majority of the boxers who fail a cannabis test probably haven’t used marijuana in weeks, maybe not since the start of training camp. When this is the case, the cannabis remaining in their system has been neutralised. No harm. No foul.

Keeping cannabis on WADA’s list of prohibited substances also deprives boxers of its medicinal benefits. Although medical science is divided on the matter, there is much anecdotal evidence to the affect that marijuana can be helpful in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)—a condition to which fighters are unquestionably vulnerable.

Boxing isn’t the only sport grappling with changing attitude toward cannabis. Of the three major team sports in the United States, Major League Baseball has by far the most liberal cannabis policy. Testing big leagues baseball players is virtually nonexistent.

“They don’t care because professional baseball has long had a public relations problem when it comes to drugs, but these “drugs” don’t include weed,” writes Jenn Keeler on Wikileaf, an online resource for medical and recreational marijuana patients and consumers. “Most of us are aware of the steroid era—the era when players bulked up and home run totals soared. It’s these performance-enhancing drugs that have the league’s attention.”

Canada has legalised recreational cannabis, so there’s little or no infamy associated with the substance in the country. With so many National Hockey League teams and players residing in north of the border testing doesn’t make any sense.

Although the National Football League has a reputation for being very conservative, Chris Long, who recently retired after playing in the NFL for eleven years, said, “I certainly enjoyed my fair share on a regular basis throughout my career. Testing players once a year for ‘street drugs’, which is a terrible classification for marijuana, is kind of silly because, you know, players know when the test is. We can stop.” Whether the publicity Long’s revelation generated will lead to a change in the NFL’s testing policy remain to be seen.

Nonetheless, if WADA could bring itself to follow VADA’s example, boxing would, for a change, be on the leading edge of progress. It’s a small thing compared to many of boxing ills, but an easy one to solve.

***

Sparrow’s bout with Lundy was the best fight on a good card. Lundy survived two second-round knockdowns, to give his young and relatively inexperienced adversary the toughest test of his eleven-fight career. There were some lively exchanges, especially near the end of the eighth round, when, much to the delight of the crowd, they traded punches with reckless abandon. The majority 10-round decision went to Sparrow.

Sparrow is a precocious talent with an aesthetically pleasing style. He can’t afford to wait for WADA to get its act together. A boxer’s career moves a lot quicker than an entrenched bureaucracy changes its regulations. From here on, Sparrow has to be careful and keep a close eye on the calendar.