“YOU’RE speaking to the perfect person, because I’ve been both sides of the fence,” says Gary Lockett on the hardest decision a trainer has to make. “Early on in my career, I pulled a few fighters out and was accused of being too gung-ho with the towel. But then the Nick Blackwell-Chris Eubank fight came around and there wasn’t a problem until Nick fell unconscious, then people wanted to start pointing the finger.”

As Lockett knows, trainers perform a tightrope act when it comes to pulling a fighter out. Do it too early and stand accused of being overprotective, as well as becoming a scapegoat for a loss; of actively turning your own boxer against you. Leave a boxer to soak up punishment and you’re labelled compassionless, the so-called brave corner. Far worse, you could see a fighter suffer serious injury.

In Lockett’s eyes, it’s a decision you’re only qualified to make “if you know the fighter really well”. He was willing to throw in the towel during Gavin Rees’ WBC lightweight title fight with Adrien Broner in 2013, going against his boxer’s wishes when the act of surrender came in the fourth round. “I disagree with my trainer stopping it,” Rees said in the aftermath. “I was always going to get back up. I was going to get keep getting up until I got knocked out cold.”

Presumably, this was exactly what Lockett wished to avoid. To this day, Rees does not accept that it was, in fact, a perfect intervention. Yet the two remain close, the ex-fighter understanding that Lockett was acting on his best interests. It is not always that simple.

In 2002, Buddy McGirt, the trainer who sparked a late resurgence in Arturo Gatti’s career, almost ended the Gatti-Mickey Ward trilogy before it was even one-third of the way through.

During the incredible, punishing ninth round of Gatti-Ward I, McGirt stood up to the ring, towel in hand, set to halt the fight. As he did so, Gatti began to fire back and – with referee Frank Cappuccino focused on the action – McGirt was able to slip back unnoticed.

“When he got hit with that body shot, he had tears rolling down his face,” said McGirt in an interview on Showtime this year, admitting he also came close to ending the fight after that round as well. “When he went out for the 10th, I said: ‘You got to show me something, baby, or I’m stopping it.’”

“His friend grabbed me by my pants and said: ‘But if you stop it, he’ll never speak to you again.’ I said: ‘I’m not going to let him get hurt – I don’t give a f*** if he ever speaks to me again or not.’ Let’s see what happens.”

What happened was Gatti dredged up the will to fight back. The incredible action and a disputed decision meant two money-spinning sequels, but it can’t be overlooked that McGirt had been willing to step in and save his hurt fighter, despite knowing it would be kissing goodbye to future pay cheques. How many trainers can say that?

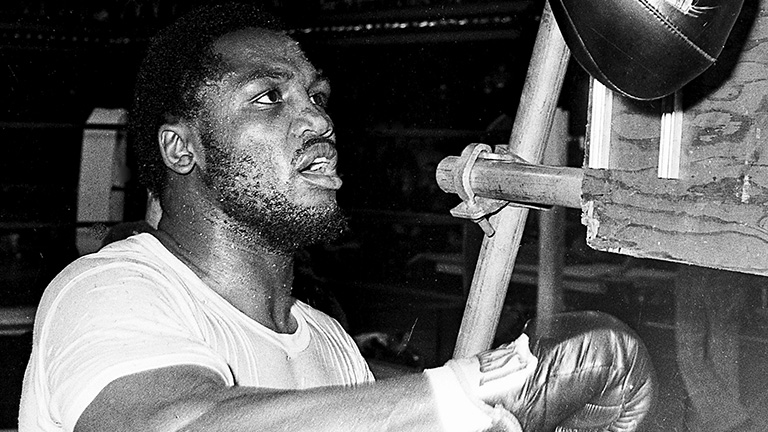

Eddie Futch could. The man responsible for the most famous rescue call in boxing, when he pulled Joe Frazier out of his third fight with Muhammad Ali in 1975, surely knew how Smokin Joe would react.

“Eddie, listen up! Whatever you do, whatever happens, don’t stop the fight!” Frazier had said beforehand. “We got nowhere to go after this… I mean it. This is the end of him or me.”

Futch was unwilling to let it go that far. His words – “Sit down, son, it’s all over. But no one will ever forget what you did here today”– became his legacy as he spared Frazier from three more minutes of punishment from Ali’s fists. Yet it fractured things between them.

According to Mark Kram’s Ghosts of Manilla, Frazier would later say: “I got mugged by the ref in the second Ali fight, and Futch took Manila away from me.” Or, even more bitterly: “He never did anything for me except collect 15 per cent of my purse. Eddie can’t train nobody. He was just there to wipe me down.”

Frazier’s seething hatred for Ali spilling on to Futch is an example of how a boxer-coach bond can break after a disputed stoppage. Lockett is in a position where a majority of the fighters he has worked with – from Rees to Kerry Hope to Enzo Maccarinelli – have eventually accepted his call to end a fight. But that doesn’t mean he hasn’t suffered.

“It’s very hard for me to talk about this,” says Lockett when it comes to Blackwell and the brain injury he suffered against Eubank in 2016. “With Nick, every fight he had he lost the first four rounds – and then he’d come back down the stretch. So with that in mind, we tried to give him as much chance as possible.

“At about the eighth round, he was far behind. So I said to him: ‘Look, I’m going to stop it’ and he said: ‘What? He can’t even punch! Why would stop it?’” Then in the 10th round, when his eye came up, I was going to pull him out – but Victor [Loughlin] stopped it anyway.”

Despite collapsing after the fight and spending a week in a coma, Blackwell looked to have made a remarkable recovery. Until – later that year and away from Lockett’s care and expertise – he chose to spar and was badly hurt once again. This time, recovery was even more challenging. Some aren’t even that lucky.

Lockett’s voice drops lower and lower as he finds the words about an even greater tragedy. “If you go six months [after the Blackwell fight], it’s something that not everybody knows, but I had Dale Evans against Mike Towell.”

This time, Lockett was in the other corner when a fighter was rushed to hospital post-fight. For Towell, there would be no miracle recovery. He was declared dead a day after the fight.

“It’s the worst thing I’ve ever been through in my life,” says Lockett. “I wouldn’t wish it upon my worst enemy.” Did either incident, running so close together, make him question if he could continue in the sport?

“I can remember, after the Blackwell fight, Liam Williams fought an eight rounder in Liverpool. I was trying not to show Liam that I was nervous, but I was just thinking: ‘What if something goes wrong?’

“When you’ve been through an incident like that, it’s very hard to shake it. Liam got the job done, but there were a few fights where I was frightened, in a way, for the boys. I kept it to myself – and after a while, it sort of passed. I still get it every now and then – I tell myself to be professional about it. But these things still come up in my little old mind. I just keep it to myself.”

McGirt can surely relate. In July, he was in the corner when unbeaten Maxim Dadashev fought Subriel Matias. “Max, I’m gonna stop the fight,” said McGirt after the 11th round. “You’re getting hit too much. Please Max! Let me do this, OK?”

Dadashev shook his head at his trainer’s pleas, but McGirt held firm. A trainer cannot officially stop a fight, of course, but few officials argue when the corner have made their opinion clear. After the fight, McGirt explained: “He had no chance of winning, so why be a hero with his life?”

It was already too late. Dadashev had collapsed and vomited on the way to the dressing room. He died in hospital four days later. It’s a heartbreaking reminder that even when a trainer does everything in their power to make the right call, stepping in ahead of a referee or doctor, it cannot always be enough.

Fast-forward one month and McGirt was in the corner when another Russian, Sergey Kovalev, fought Anthony Yarde. After Yarde’s eighth-round comeback that saw him tee-off on Kovalev, McGirt read the riot act in the corner.

“Listen! If you take more shots like that, I’m stopping it – you understand? I’m going to give you this round to show me something! I know he’s tired, but you’re getting hit with too many punches.”

Were McGirt’s words a ploy to shake up Kovalev; to get his charge boxing behind his jab once again rather than getting into exchanges with a young puncher? Or was McGirt thinking of Dadashev and battling what Lockett spoke of; that little voice in your head, nervous, post-tragedy for a different fighter? In a conversation with Boxing News last month, McGirt admitted it was a bit of both.

The outcome on this night was successful for McGirt and his boxer. Yet a trainer’s responsibility never lessens. Few other coaches in any sport head into a contest focusing mainly on a winning strategy but also aware, deep down, they might have to make a life-or-death decision in the heat of battle – that they themselves could be the final instrument that triggers a defeat.

It’s a heavy burden to bear. But those who feel it the most deeply, from Futch to McGirt to Lockett, are in fact the people any boxer should most urgently want in their corner – a trainer with the courage to quit when the time is right.

Throwing in the sponge

Chucking in a towel – the white flag of surrender – might seem an appropriate signal for capitulation. But the original phrase, from the 18th century, was to “throw in the sponge”, a sponge the most common item a corner would use to wipe down a pugilist between rounds.

One of the first recorded reports of a thrown towel came in a January 1913 edition of US newspaper The Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette: “Murphy went after him, landing right and left undefended face. The crowd importuned referee Griffin to stop the fight and a towel was thrown from Burns’ corner as a token of defeat.”

Yet the practice was already established. One early corner stoppage in a high-profile fight came in Jack Johnson’s 1910 heavyweight title bout against the “great white hope” brought in to dethrone him, Jim Jeffries. With Jeffries badly hurt – and ringside spectators crying: “Don’t let the n****** knock him out” – one of Jeffries’ seconds, Bob Armstrong, entered the ring with a white towel to end the fight. Occasionally, referees have ignored a trainer and thrown a towel back out of the ring. Graham Earl’s corner threw in the towel during his 2007 fight with Michael Katsidis, only for Mickey Vann to remove it. Earl knocked Katsidis down shortly afterwards, although was eventually retired by his team after the fifth round.