THE family of record-holder Len Wickwar want him to be remembered in his home city. The Guinness Book of Records and every boxing encyclopedia includes Wickwar’s name. He’s there because he had more professional fights than anyone else.

BoxRec and The Ultimate Encyclopedia of World Boxing can’t agree on the exact number – the former reckons 470, the latter says 460 – but they are agreed that nobody had more.

Turning pro at 17 in 1928, Wickwar fought until 1947 and with a six-year gap for World War II, he fought on average around every nine days throughout his 12-and-a-half active years. BoxRec record him fighting an astonishing 58 times in 1934.

“If it wasn’t for the War,” said son-in-law Bryan Spencer, “I’m sure Len would have had 600 fights.”

Spencer wants Wickwar to be remembered in Leicester, where he lived his 69 years until his death in 1980. Spencer says that with factories built on the area in the East Midlands city where Wickwar grew up, the rugby ground on Welford Road, home of Leicester Tigers, is an option for a plaque. That was where Wickwar fought then-British lightweight champion Eric Boon in a non-title fight in front of 14,000 fans in July, 1939. Brief footage of the fight is available on YouTube. Wickwar lost in nine rounds – and blamed the weather.

“Len was never one for excuses,” said Spencer, “but it was throwing it down with rain during the fight and he always said they should have stopped the fight.

“The canvas was so wet, Len said it was like an ice rink.”

Spencer had known Wickwar since 1964, when he met Len’s daughter Pearl, until his death and regarded him as “the best mate I ever had.” They worked together at Bentley Engineering – Wickwar was a packer and labourer – and were neighbours on the New Parks estate in Leicester. Spencer says Wickwar had little interest in boxing once he had retired. “People would ask him to help out at the gym,” he said, “but Len never wanted to know.

“I’m sure he could have been a good trainer, but Len used to say: ‘I’ve done my time, I’m finished with boxing.’

“He never went to any shows. He had seen it all and done it all. He was glad to walk away from boxing.”

There was bitterness towards his former manager, George Biddles. He wrote of the “adventures” they had together, but Wickwar remembered things differently. “I remember Biddles coming round the house one Christmas and Len didn’t want to know,” said Spencer. “Biddles wanted to come in for a couple of hours to chat and Len told him to p**s off.”

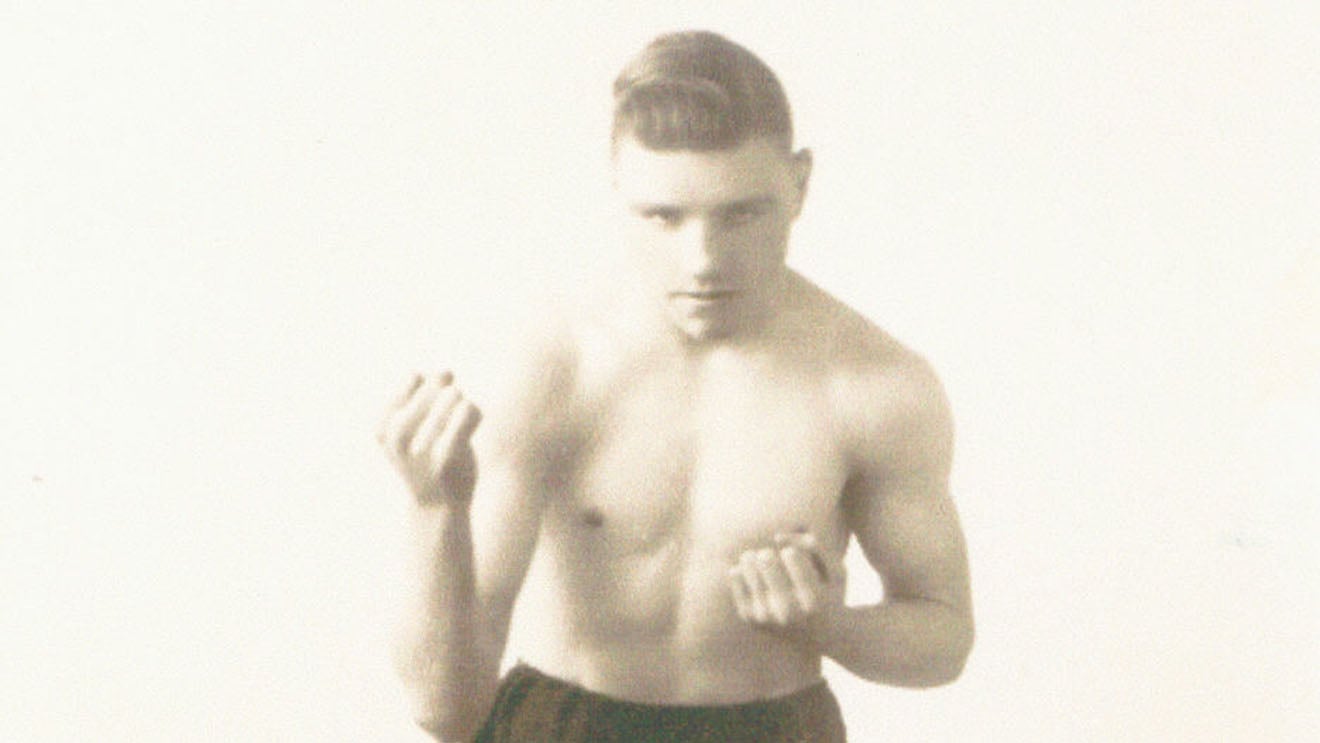

Biddles told Boxing News in his memoirs that he discovered Wickwar at a gymnasium above the Friar Tuck pub, not far from where Rendall Munroe would learn to box years later. Biddles remembered seeing “a quite clever and experienced boxer sparring with a young lad who was in his short sleeves and long trousers and who to my utter surprise, was completely outboxing the experienced professional.

“I waited until the sparring was over and then called the young unknown across to me.”

The “young unknown” gave his name as “Leonard Arthur Wickwar” and Biddles asked him where he had been training to become so accomplished.

“Nowhere, I often box with Bill (Newbold),” answered Wickwar. “He lives next door to me.”

Leicester was, still is, a hard city and when Wickwar turned pro, times were especially tough. “Fellows would fight because they needed the money badly,” wrote Biddles – and there were thousands of professionals.

Biddles kept his stable busy. Bert Tiger Ison had 335 fights – including 16 against Wickwar. Len won 15 of their fights. Wickwar also lost over 12 rounds to Chelsea bus conductor Billy Bird, who had a reported 356 fights, and proved he could compete at the highest level.

There was a 12-round points loss to Freddie Miller, who held a version of the world featherweight championship in the 1930s, a disqualification loss to Jack ‘Kid’ Berg and Wickwar edged his five-fight series with British welterweight champion Pat Butler 3-2.

Wickwar fought regularly on Biddles’ shows and one night in February, 1929, at the Tramways Institute in Leicester, he fought three times, outpointing Tommy Cann, Len Swinfield and Bobby Wood over three, four and six rounds respectively.

“He was only getting a pittance for fights,” said Spencer. “He probably got more than he did for working a day in a factory, but not much more. I’m sure he boxed because he enjoyed it, not for the money.”

Wickwar didn’t appear to end his boxing career with much money. He pawned one of his belts, Len won a Midlands featherweight belt competition and the Midlands Area welterweight title, and another was stolen from the Ragdale pub where he was happy to drink anonymously in retirement.

Spencer is too young to remember Wickwar boxing, but Harold Varnham saw him a few times towards the end of his career. Varnham says his father started taking him to boxing shows in the city in 1946 and he remembers Wickwar as “a superb boxer.”

He said: “Len was skinny, all his family were skinny, and it looked like you could blow him over like a feather. But he was a superb boxer. He went in there with the intention of not getting hurt.”

Those who remember Wickwar remember a quiet, modest man who liked the occasional flutter on the horses – and had a strong work ethic. “Len never wanted to retire from his job,” said Spencer, “but they made him.

“He liked being there with the lads. When they took his job off him, they took away a big part of his life. I remember Len coming home from work on his last day and throwing his bike in the shed – he was forever cleaning and oiling that bike – and he went downhill after that.”

Wickwar was happiest when spoiling his grandchildren, Wayne, Mark and Mitchell, who had “two or three” for Belgrave Amateur Boxing Club. Spencer says Wickwar’s family ties meant he turned down the chance to fight in the States. The offer was made, but Wickwar didn’t want to be away from wife Phyllis and children Leon, who passed away a few years ago, and Pearl, who celebrated her 75th birthday recently.

Spencer says in the years he knew Wickwar he only rarely struck a boxing pose or showed off a move, but he was happy to reminisce with Boon when his former opponent came to Leicester in 1974. In retirement, Boon travelled the country raising money for charity by showing films of big fights and when he brought his projector to a social club in the city he shared memories with Wickwar of the time they fought in front of 14,000 fans on a rainy night at the rugby ground.

Cut under his left eye early on, Boon took charge and dropped Wickwar for a count of ‘nine’ in the fifth. Wickwar toughed it out and briefly threatened a rally that was halted by a short right hand in the ninth round. This time, he didn’t beat the count. Boon afterwards revealed he had hurt his right hand earlier in the fight and the following morning, Wickwar drove him to the hospital for an X-ray.

This story backs up every other testimony of Wickwar. He was a decent man. Biddles did hope for a rematch with Boon, but the fight didn’t materialise and Wickwar spent the war working in a clothing factory. He would fight only four times after the war, retiring after a five-round knockout defeat against Danny Cunningham in Newcastle in February, 1947, a month shy of his 36th birthday.

“There were young lads who were handy with their fists who were coming out of the Army and thought boxing was an easy way to make money,” said Spencer. “Len decided it was a good time to finish.”