“FOR everything to stay the same, everything must change.”

Used to set the scene for a tale about the decline of a family of Sicilian aristocrats in the 1800s, this line from Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s 1958 book The Leopard also summarises where boxing found itself a year on from Floyd Mayweather vs Conor McGregor.

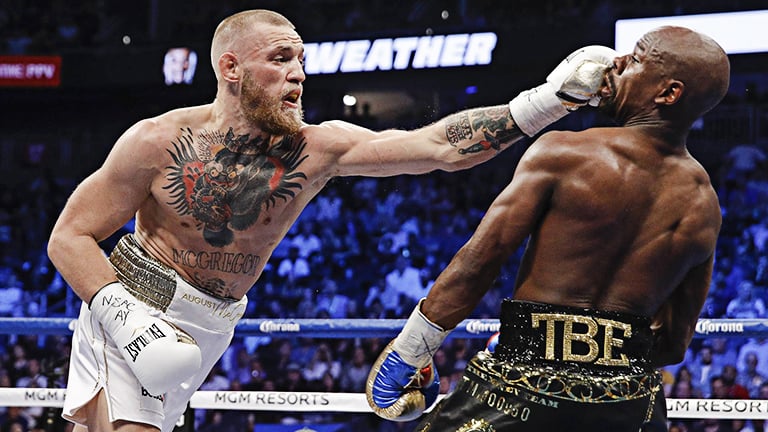

Change. How we feared it. Twelve months ago, the concern was that Mayweather vs McGregor, this cheap shot of a fight, would disfigure the face of boxing beyond all recognition; that it would apply to a face already replete with black eyes further blemishes so severe, so ghastly, the damage would be irreparable. Such thoughts were unavoidable. Lunatics, we felt, had taken over the asylum.

Only the reality, we now know, was quite different. Rather than create a new world order, Mayweather vs. McGregor was instead a combat sports colonic irrigation; the wrecking ball both boxing and mixed martial arts needed to kickstart a rebuilding process. To our surprise, a great truth followed a great lie, and the August 26 fight ended up hurting neither fighter, nor either sport.

If reluctant to revisit it, here’s what we know happens when Conor McGregor, a mixed martial artist, shares a boxing ring with Floyd Mayweather, a boxer: it’s one-sided, it’s unfair, it’s man against boy, it’s up to the boxer to decide when and how it ends, it’s as painful or painless as they want it to be, it’s at times embarrassing, it’s anticlimactic, it’s self-indulgent, it’s financially rewarding (for them, not us), and it’s all a big, fat waste of time (for us, not them).

Some required nine-and-a-half rounds and a 10th round stoppage to reach this conclusion, while others, those who detected Mayweather’s need to delay the inevitable, cracked it from the outset.

Still, McGregor, to his credit, tried at least. He played his part, both in the event and the fight, and had more success – in the fight, that is – than most expected. There were pitter-patter combinations thrown at a stationary target, for instance, and an uppercut in round one. He did enough to get people unfamiliar with ring generalship and technique excited about his chances. Some even awarded him rounds.

Where McGregor failed, however, was in convincing us he was a boxer. Not only that, his pro debut emphatically slammed the door shut on any hope he had of continuing the masquerade, a genuine worry beforehand, and exploiting subsequent collaborations with boxers more suitable.

Boxers like Paulie Malignaggi, for example, the sparring partner with whom McGregor constructed a less-than-organic rivalry in the weeks preceding the Mayweather fight. That one, in terms of a McGregor redemption story, seemingly had it all: the history, the hatred, the sparring sessions, the punch-push knockdown, and numerous social media exchanges. It was cooking away in the background while McGregor, on camera, talked the audience through the ingredients for his Mayweather dish. “And here’s one I made earlier,” he might have said. Then out pops Paulie.

Of course, that it never happened says all you need to know about McGregor’s trial run against Mayweather on August 26, 2017. For had there been even the slightest bit of momentum behind it, a hint of an opening, or a slither of money-making potential, there’d be no question McGregor, 0-1, and Malignaggi, 36-8 (7), two shrewd prizefighters who understand the model, would have tried capitalising on it.

Alas, the recipe lacked something. After the hype, and the first-round uppercut, came the water torture, administered by Mayweather and endured by McGregor (and everyone else). It left McGregor with the expression and anxious breathing pattern of an infant lost in a supermarket, and left Mayweather, a master of the 12-round distance, joyfully skidding down the aisles on his knees as if the supermarket was in fact his home. It was easy for the boxer. Easier than any other fight he’d had. Easier than any sparring session he’d had. Easier, it must be said, than his 50th professional fight had any right to be.

It concluded perfectly, too. For the two of them, and for us. Prolonged to perfection, there were enough rounds, nine-and-a-half, to ensure the intended audience didn’t feel short-changed, and the success of the boxer, the man whose house the mixed martial artist rudely gate-crashed, was vital in order for both sports to continue as before.

We all left feeling relieved. Wiser for the experience, sure, but ultimately unchanged. Mayweather slinked back into retirement with his 50th win and a hefty asterisk attached to an otherwise faultless boxing record, while McGregor, still the UFC lightweight champion, eventually returned to MMA. (His comeback fight, a difficult one against Russian Khabib Nurmagomedov, was booked for October in Las Vegas.)

As for the Mayweather vs. McGregor impact on boxing, there was none. If anything, so disappointing was the spectacle, any talk of follow-up crossover fights swiftly died a death, and, best of all, purists now have a reference point whenever anybody dares mention the possibility of a mixed martial artist boxing a boxer. They’ll shout the date: August 26, 2017. They’ll pull up the image of McGregor, MMA’s premier export, exhausted and fleeing from a semi-retired 40-year-old focused more on damage control than old-fashioned damage. They’ll then say, “Remember this?”

Frankly, Mayweather vs. McGregor wasn’t so much the start of a movement as the disease that wiped out a population of likeminded chancers. It’s why there hasn’t been another since. It’s why social media flirtations between UFC bantamweight champion TJ Dillashaw and boxing hotshot Gervonta Davis will never take them to second base. And it’s why even fewer mixed martial artists will try their hand at boxing – and vice versa.

Perhaps inadvertently, by some glorious twist of fate, the fight designed to bring together two vastly different combat sports, all in the name of making ungodly amounts of cash from a faulty and falsely advertised product, has actually conspired to push them even further apart. “Two different sports,” we’d hear experts say prior to Mayweather vs. McGregor. Well, now we know. We have all the proof required. The case, the one full of money, has been closed.

Even so, Mayweather vs. McGregor did manage to achieve a couple of things that will presumably stand the test of time. Firstly, it reaffirmed the importance of bad blood and all-round nastiness, fabricated or otherwise, when selling fights. And secondly, it reminded boxers and mixed martial artists of the need to be seen and heard in this digital age. Don’t be quiet. Don’t let your fists do the talking. Don’t prove yourself the antiquated way with titles and signature wins. Instead, go out there, the MayMac monster said, and make something happen. Be controversial. Say things you’d never normally say. Do things you’d never normally do. Wear a mink coat. Wear a cash-filled rucksack. Be a d**k. It worked for Mayweather, it particularly worked for McGregor, and it can no doubt work for you, too.

In many ways, Mayweather vs. McGregor was to fledgling fighters what a Kardashian backside is to impressionable young girls. (Thankfully, August 26, 2017 was the day the implants burst.) For better or worse, it crystallised the notion that popularity contests are the big money-makers in combat sports and made it clear, beyond any doubt, that a person’s fame now enables them to bank monstrous paydays doing a sanitised version of something others do for real.

***

So far, the clearest offshoot of Mayweather vs. McGregor isn’t a boxer vs. mixed martial artist sequel but a white-collar boxing match between YouTubers Olajide William Olatunji (better known as KSI) and Logan Paul, which became a reality on August 25, pretty much a year to the day that Mayweather and McGregor counted money in a Las Vegas ring.

Though out of place in Boxing News, this event becomes noteworthy because it was clearly inspired by Mayweather vs. McGregor and because there’s every chance it will be the most-watched ‘boxing match’ in Britain this year. If it needs explaining – and I hope it does – here goes: KSI has 19 million subscribers on his YouTube channel, the apparent appeal of which is watching him play games of FIFA, while Paul, thanks to his vlogs (video blogs), has 18 million on his.

In short, they are famous. Not famous in the way people used to be famous but famous in the way people today tend to be famous. They’re famous online, followed and worshipped by an audience of millions, and therefore capable of making money in the simplest way possible: by being themselves; by walking, talking, eating and gaming; by fighting.

Suffice to say, boxing let them in. Post-Mayweather vs. McGregor, there’s no moral high ground to speak of, let alone quality control, and the language of the fist-fight remains universal. Indeed, you could go so far as to say boxing’s simplicity is both a blessing and a curse at this stage. It makes the sport enticing and compelling, no question. But, equally, it makes it vulnerable, accessible and easily exploited. Essentially, anyone can do it.

Case in point: the meeting of KSI and Logan Paul wasn’t sanctioned by the British Boxing Board of Control, and wasn’t even a professional boxing match, yet still managed to sell out the Manchester Arena, to the tune of 20,000 tickets, and generate the kind of figures, both on YouTube pay-per-view and social media, that were the envy of so-called conventional boxing promoters.

Undoubtedly enterprising, it thrived outside the trade for no other reason than it was a fight and human beings like and understand fights. It wasn’t a game of golf, a game of tennis or a game of cricket. It didn’t require knowledge or expertise to follow. Those watching cared little about qualifications, intricacies and licences. They saw only famous faces and fists.

Moreover, the machine is by now tried and tested. A video of KSI’s previous ring outing in February, for example, has racked up 17m views on his YouTube channel, which, compared with the 5.6m who have watched Anthony Joshua vs. Wladimir Klitschko via Sky Sports’ official YouTube account, paints quite the picture.

It tells us internet fame trumps talent and titles. It says, quite explicitly, that fighting, because of its universal appeal, will always attract different audiences with different expectations and that the disparity between what’s authentic and what’s counterfeit won’t necessarily reflect in the numbers. In essence, just as a fake designer handbag is still a handbag, so a manufactured fight is still a fight.

Ultimately, incidents like KSI vs. Logan Paul and, to a lesser extent, Floyd Mayweather vs. Conor McGregor, aren’t so much boxing matches as examples of famous people throwing punches. Nothing more, nothing less. All a bit of fun. No harm done (seriously, no harm done). Yet the one concern, fuelled by a growing temptation to market the sport in this way, is that the concept, as simple as it is appealing, will soon become more popular and profitable than the art on which it’s loosely based.

It’s then a more appropriate quote from The Leopard might be this: “We were the leopards, the lions, those who’ll take our place will be little jackals, hyenas; and the whole lot of us, leopards, jackals, and sheep, we’ll all go on thinking ourselves the salt of the earth.”