SIX years ago, Boxing News ran a cover dominated by an image of a topless Saul “Canelo” Alvarez accompanied by the coverline “Lawless”, which essentially teased an in-depth investigation into the Mexican’s two failed performance-enhancing drug tests ahead of a planned fight against Gennady Golovkin on May 5, 2018.

Fast-forward to today, meanwhile, and Alvarez finds himself again gracing the cover of Boxing News, only this time his behaviour – that is, his career – is celebrated as the coverline reads: “Far From Finished.”

Indeed.

Six years, you might argue, is a long time, and maybe by now it’s only right that Alvarez, a fine fighter and dominant champion, is forgiven and that his transgressions be forgotten. But what isn’t a long time is six months, which just so happened to be the length of the ban Alvarez served for clenbuterol being in his system before a scheduled prizefight in 2018. When taking into account, too, the fact that Alvarez, as the sport’s biggest money-maker, need not ever fight more than twice a year, six months merely amounted to the typical time he might take off between fights.

“What really bothers me is that the test was in February and I have at least three tests in my records where Canelo was negative,” WBA president Gilberto Mendoza told me in Cardiff on March 29, 2018, just three weeks after the Canelo news broke. This also happened to be roughly half an hour before, in the exact same room, I interviewed renowned drug cheat Alexander Povetkin ahead of his heavyweight fight against David Price and discovered the Russian had been tested not once before arriving in Wales. “So why are you going to stop the (Alvarez vs. Golovkin) fight happening?” Mendoza continued. “Is it to do with marketing the fight? I don’t understand it.

“I consulted specialists in that field and the percentage of clenbuterol he had gives you reason to doubt. I just don’t see it. I stand by Canelo 100 per cent. This is a fighter who has never had a positive (drug test) in the past.

“It’s like if something happened to Anthony (Joshua). These guys carry the torch for the sport. They are the reason we exist. Fans, sanctioning bodies and the rest of the fighters owe it to them. If you look at their careers, they have been clean all the time. But sometimes, at some point, I understand, things can happen.”

Keen not to come across as rude, I remember doing my best not to laugh that day, or even open my eyes too wide. Yet it was difficult not to again be taken aback by the words of the players involved in this self-satirising sport. It was also difficult not to feel that Mendoza’s laidback approach and loose tongue owed in large part to a belief that he knew that everything would soon sort itself out and that a boxer as commercially valuable as Alvarez, and as important to the sport as Alvarez, would in the end be absolved and allowed to continue providing for the many outstretched hands he must both shake and fill during any big fight week in Las Vegas. Come September, in fact, it was true: all was forgotten. With his ban already served, Alvarez was indeed fighting again; not just fighting again but again fighting Golovkin, his great rival.

Canelo Alvarez (Sarah Stier/Getty Images)

Six years on, he is still at it, too. Still winning fights and still adding to his already impressive legacy, the revered Mexican is reminded of past transgressions only by his enemies, as demonstrated this week thanks to Oscar De La Hoya, or, as demonstrated later that same day, by the transgressions of his unruly peers.

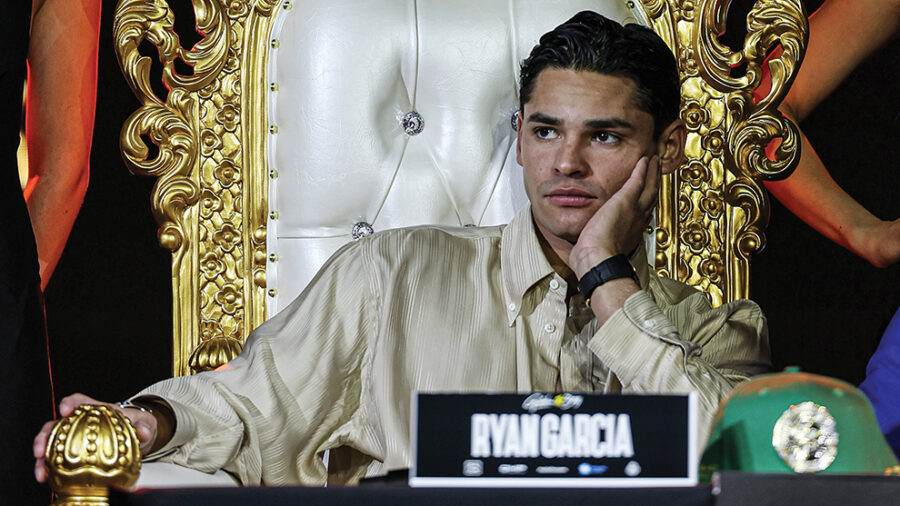

By unruly peers, of course, I specifically mean Ryan Garcia, the 25-year-old teenager about whom a million didactic social media posts were written yesterday (May 2) following news of two positive performance-enhancing drug tests. The first of these positives arrived on April 19, while the second arrived on April 20, the very day of Garcia’s fight against Devin Haney; a fight he won by decision, having floored Haney a total of three times and in the process fractured his jaw.

The drug for which Garcia tested positive, by the way, was Povetkin’s old favourite ostarine, a selective androgen receptor modulator (SARM) banned both in and out of competition by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) and typically used to boost muscle mass, aid weight loss and improve athletic performance. It was also reported that Garcia tested positive for 19-Norandrosterone, a metabolite of the banned substance nandrolone, with further analysis pending.

Of no surprise to anyone, Garcia has of course professed his innocence and denied knowingly taking any banned substance. He has, in a tactic used by others in recent times, even insinuated some kind of witch hunt or foul play, as well as identified ashwagandha root, a herbal supplement used to relieve stress, as a potential cause for the positive tests. (There are videos and tweets; all of which, if we have learned our lesson, should be ignored and avoided.)

Ryan Garcia (Roy Rochlin/Getty Images for Empire State Realty Trust)

Whatever the truth, the only shock bigger than the result of Haney vs. Garcia was the fact that nobody, as far as I’m aware, proposed the possibility that the winner, a man advocating the use of substances throughout his training camp, might test positive for a performance-enhancing drug at some stage. In hindsight, this now seems not only an inevitable outcome but arguably the most fitting way for a frankly repulsive fight/rivalry to conclude and be brought to its knees. It represents, in so many ways, both the final insult and what everybody involved deserved; either for the death threats, the bizarre social media conduct, the collective turning of the cheek, or just the sheer unsavoury nature of it all.

Taken further, one might even suggest that it isn’t just the ending the rivalry deserved but the one it perhaps needed. That is to say, Haney vs. Garcia needed an ending like this just to restore some sort of equilibrium; restoring, at the same time, at least some of us to sanity. Otherwise, without it, this denouement, we were all in danger of being manipulated into thinking we had got it wrong, or that we were in the wrong, and that by allowing ourselves to be “duped” by Ryan Garcia’s apparent mind tricks we were somehow all gullible, naïve, or lacking intelligence. Meanwhile, Garcia, the so-called genius of the piece, nonchalantly rode off as the hero, described by some, purely on account of the volume of rubberneckers his rotten behaviour had attracted, as both the “future of boxing” and the “face of boxing”. If indeed that is true, it’s worth remembering now that it’s not the face on the cover that counts. It’s instead what you see in their eyes; where the truth never hides. It’s also what’s written on the page. The titles. The names of beaten opponents. The weight classes conquered. And yes, the drug tests failed.