ON Saturday July 26, 1890, a challenge appeared within the pages of the Sporting Life with the following words, “Harry Peter of Islington says he is surprised at Joe Caly challenging him for the third time, he having already defeated him twice, once with the raw-‘uns and once with two-ounce gloves. Peter, however, will have much pleasure in meeting Caly at the Crooked Billet, Ponders End, to sign articles for a match”.

Not only does this show how matches were made in those days, with challenges being issued daily in the sporting press and matches being agreed in public houses, but it also reveals that professional boxers were concurrently engaged in fights with the bare knuckles, under the old rules, and with gloves, under the Marquis of Queensberry rules.

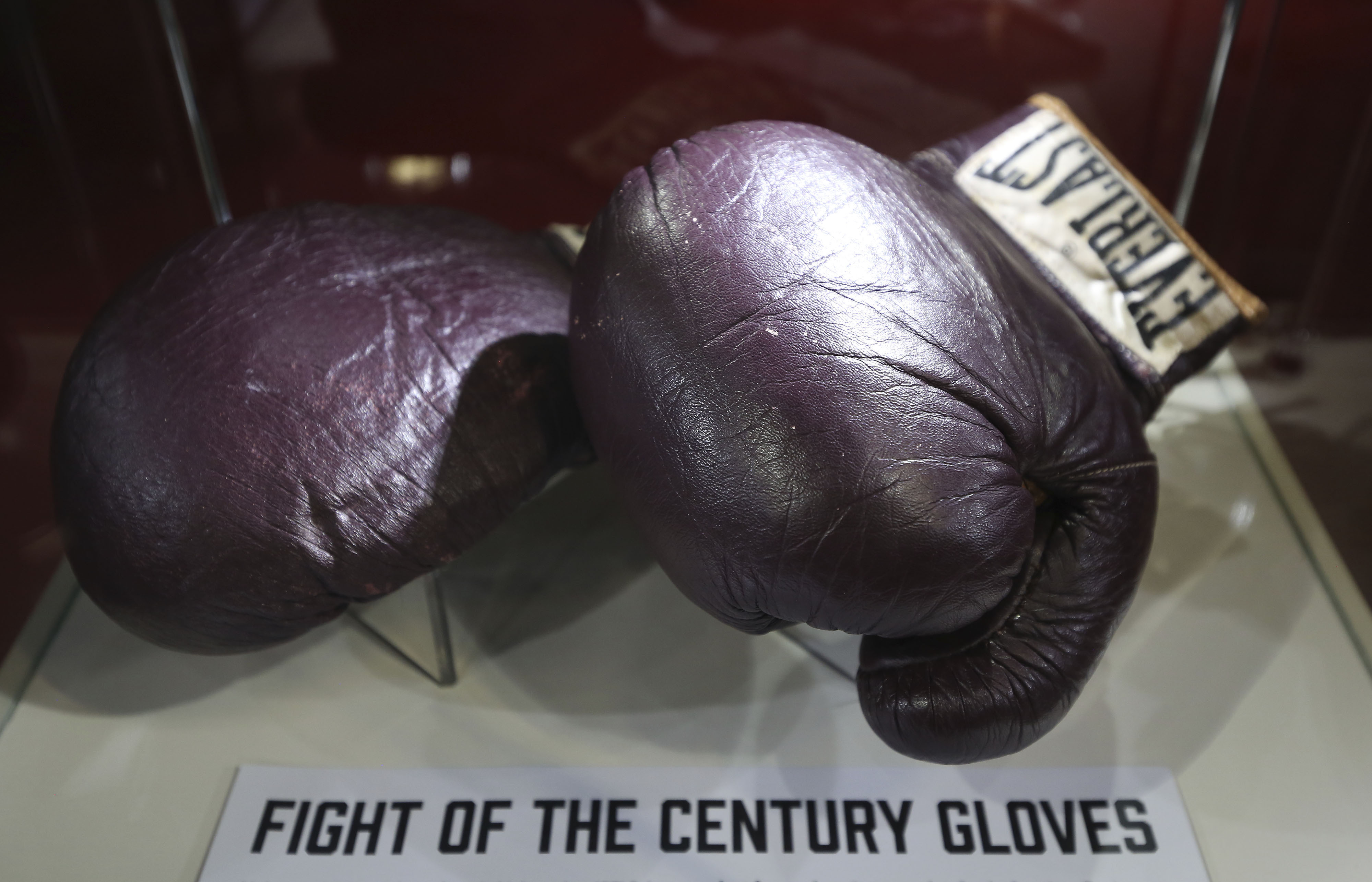

Modern readers will be surprised at the use of two-ounce gloves. During this period, it was common for boxers to agree to fight each other with the “small gloves”, at two ounces or with the “normal gloves”, usually at four ounces. During the next 20 years, until the beginning of the first world war, four-once gloves were the most commonly used.

The gloves would be filled with horsehair, and they were lethal if they encased the hands of a big puncher. Even for the little men who did not punch that hard, the cumulative effect of hundreds of blows delivered over the course of 15, and frequently 20-round contests, was very damaging and contributed largely to the many instances of punch-drunkenness that so many boxers of this era fell victim to.

Before the advent of the Board, and its rules and regulations, negotiations concerning the size of the gloves to be used fell to the boxers and their respective camps. I recently wrote about the great contest between Freddie Welsh and Jim Driscoll, which took place at Cardiff in 1910.

The articles of agreement for this match stated that the match would be made at 9st 6lbs, the boxers having compromised when Welsh preferred 9st 7lbs and Driscoll, 9st 5lbs. The wrangling over the gloves was more heated, the pair eventually agreeing on five ounces after Welsh who wanted four-once gloves, and Driscoll who preferred a six-ounce pair, eventually compromised again.

By 1929, when the Board published its first rule book, regulation 30 stated that a contest would use the rules of the old National Sporting Club and that boxers must box with gloves “to be a minimum weight of six ounces each”. It was acceptable, therefore, for boxers to agree to wear a heavier pair, with, it seems, no limit, but that four-ounce gloves were outlawed.

At the inquest for Louis Hood, who had died during a contest with future British featherweight champion, Charlie Hardcastle in 1916, Peggy Bettinson, the general manager of the National Sporting Club, stated that the gloves used during the fatal contest were six ounces, “the usual weight for contests of all kinds unless the men are very small, when they may be lighter”.

It was very common in 1916 for professional boxers to be active at the age of 13 or 14 and it may have been these lads who were permitted to use the small gloves. It also seems likely that some flyweight contests still permitted the use of four-ounce gloves at this time.

In a 1952 BN article, veteran 1930s fighter Frank Moody recalled that when he fought Larry Gains in 1923 the two men agreed to wear eight-ounce gloves because Larry’s hands would not fit into a smaller pair. Despite this, all of Larry’s important contests throughout the 1930s were fought with six-ounce gloves.

Eight-ounce gloves became standard for all men at welterweight and above as late as the 1970s. I have spoken to quite a few veterans of the 1960s and 1970s who remember using horsehair, six-ounce gloves. Today, eight-ounce gloves are used for all contests below welterweight, and 10 ounces for those above. One hopes that the game is safer, and less damaging, as a result.