By Steve Bunce

THE bus left from the side of Madison Square Garden and at that point I had never been inside the building. I was surely the only Garden virgin on the bus.

It was early November in 1989, it was bitterly cold and the Saturday before in Atlantic City, Evander Holyfield had stopped Alex Stewart in a bloodbath. It is one of the lost heavyweight fights, a testimony to Holyfield’s desire to fight anybody at any time.

The bus was going to the Poconos, to the training camp for Gentleman Gerry Cooney. The heavyweight had a fight with George Foreman scheduled for the January in Atlantic City. It would end in two, be the last fight of Cooney’s career and just the 67th fight of Big George’s endless life in the ring.

The journey was not about the fighters, it was about the boxing royalty that got on the bus: Gil Clancy made the journey. It was a name drenched in so much boxing history. And a bit of blood. Clancy was working with Cooney for the Foreman fight; Clancy had worked with Foreman after the Rumble, which is a part of Foreman’s vanished years.

On the bus, Gil Clancy was sitting in front of me, the bus was next to the Garden, and I was going to interview Cooney, who was fighting Foreman. Get in, my son. Also, in my excitement, I had filed about 1,000 words to the Sunday Express about the Holyfield fight; not one word of it would ever see print and not one penny would be made from the trip.

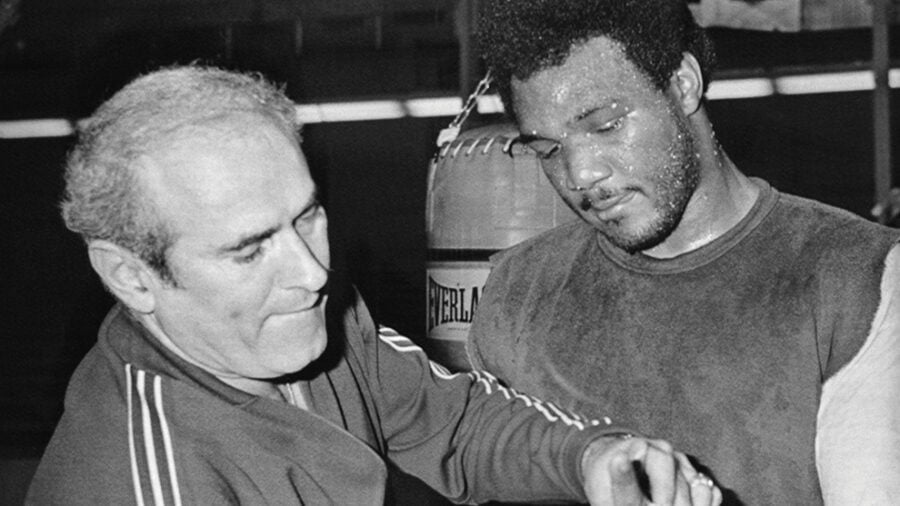

I guess Clancy would have been in his mid-sixties that day. He was distinguished looking, the man from a thousand photographs when trainers wore shirts, ties and hats. On fight night the starched jackets came out; the pockets packed with magic. The fighter’s name was stitched on the back. They always seemed to have a hand on the shoulder of a fighter. “This is my guy,” is what that reassuring touch meant.

Some of the New York writers, the boss scribes as Don King dubbed them, were on that bus for the short boxing beano to Caesars in the hills. Mike Katz, with his filthy neck support, shuffled on and Phil Berger was also there. I had met Berger, who wrote so eloquently for the New York Times, at the Holyfield and Stewart fight. I had actually written him a letter, telling him I was going to the fight and had asked if I could grab a few minutes with him. It could have been 1939, not 1989. He gave me an audience, by the way.

Clancy talked on that bus, and I tried to listen. A lot of people were listening. And he did say things like: “He’d knockout a horse if he hit it clean.” It was a compliment to a variety of fighters. He continued talking, the bus went in and out of a filthy tunnel and he talked some more. The city, the suburbs and whatever New Jersey could throw up was left in the wake of that wayward boxing bus. Then he mentioned Emile. His Emile, the Emile Griffith of boxing’s highest table.

He talked of the three fights between Griffith and Benny Kid Paret, the route to the world title fight and the aftermath. The death fight was in 1962, just 27 years earlier. No wonder the memories were so fresh and vibrant that day on the bus and on the visit to Cooney’s training camp. The bus journey was 34 years ago, and those memories have remained solid. I can sense the pauses, the hushed silences as all ears strained to listen. It was never a simple route. A simple story. Emile had to take a risk, to beat a ferocious guy, then Paret’s people needed to be coaxed. A fight was all about moving parts and men talking in private. They had three fights; one each and then the last one.

“It was sad, unfortunately Benny died.”

This was the great Gil Clancy recalling details of arguably boxing’s most famous death fight. He talked about teaching Griffith from the very start, the first day in the gym, the first steps, balance and first jab. I’m sure he had told the tale a zillion times and would tell it again endlessly until his death. Angelo Dundee did the same with Muhammad Ali tales and Manny Steward did it with loving stories of a young Tommy Hearns. In Sheffield, even after an ugly split, Brendan Ingle still got emotional when talking about the “Naz fella”. It’s in the nature of the greatest coaches to tell the story of their greatest creation. They have that right.

There was mention of Carlos Monzon, Jose Napoles, Dick Tiger, Nino Benvenuti and a dozen other names spread over a long, long period. All the names, all the great locations and Clancy was in his realm. Later, he praised Gerry, the pair sitting on the edge of the ring and Cooney blushing as Clancy talked him up. That was some trip.

In January of 1990, Cooney was blitzed in two and never fought again. Foreman regained the world title four years later. Clancy died in 2011. He was a teacher of the boxing arts, a man devoted to his craft.

A man like Clancy now would walk through the door of any gym, put his hand on the shoulder of any fighter. It would be calisthenics, as Clancy said, and then the teaching of the art of boxing would follow. A man like Clancy now would be a very wealthy man.