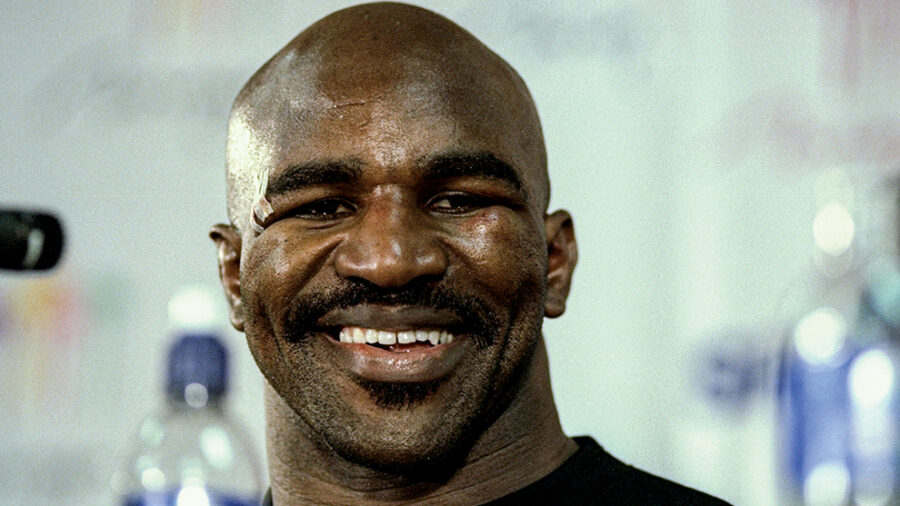

By Steve Bunce

THE Holy Warrior Invasion Tour started 48 hours before Evander Holyfield went looking for revenge in his rematch with Michael Moorer.

The venue for Holyfield’s turn in the pulpit was a little league ground called Cashman Field in Las Vegas. It was the Thursday night before the fight, and it was November. A crowd of just under 10,000 had come out for a night of prayer and song; Holyfield was the main attraction. He also had a cold and promised to only say a few words.

Moorer had not been impressed when he was told earlier that day about Holyfield’s plans to preach. “He’s made a mistake, he’s looking past me,” he said. Moorer had the IBF belt, Holyfield the WBA version; it was Holyfield’s first fight since Mike Tyson had taken a chunk out of his ear. The ear, by the way, looked fantastic. Moorer was in turmoil; Teddy Atlas was gone, and Freddie Roach was in to train him. The following day, Moorer would weigh in with his belly hanging over his underpants. He could have done with some of Holyfield’s spiritual guidance.

It was cold that night. A list of local preachers – it was a non-denominational congregation – had taken to the stage to praise Brother Holyfield for his devotion and his cash. One of the reasons for the religious gathering was to raise money and awareness for the city’s growing homeless problem. Holyfield had paid 300,000 dollars that week to feed and clothe some of the homeless. It was a growing concern for the men and women packaging the Las Vegas dream.

The crowd on the night was a mix, a real mixture of people from the city. There were a lot of poor people of all colours, sizes and ages; they were clearly struggling. They were the Las Vegas invisible tribe. It was obvious very quickly that this small trip away from the air-conditioned corridors of the casino retreats was not a publicity stunt. The hymns and prayers and endless hallelujahs could not hide the need of the people gathered. Holyfield had his flock and not many of them would be ringside two nights later at the Thomas and Mack. The far side of life in Las Vegas is so cleverly concealed that many fall in love with the neon lights and never come close to glimpsing the gloom; the homeless villages are enormous.

“The Bible says ‘Old men will dream dreams’. That’s what I’m doing, and I will keep dreaming because when people tell me I must be crazy to keep fighting I tell them they must be crazy not to follow the Lord,” said Holyfield. The pulpit was his pulpit and there was no chance he was coming down after a few words. No chance. His wife, Janice, who organised the event, was gazing at him in love and adoration. Excuse my ignorance, but I’m not sure where Janice sits in the marital chart of Holyfield’s life. That November night, she was number one.

“If I had quit boxing, I wouldn’t be the man I am today,” said Holyfield. “If I had quit the Lord, I wouldn’t be the man I am today.” Holyfield’s faith in his boxing ability could convert anybody; he had lost heavily, suffered a heart attack in the ring, broken the bully in his Mike Tyson fights and still he kept winning. He was his own fighting miracle and his words that night mattered. His cold was getting worse as the minutes ticked. He preached for 51 minutes.

Holyfield’s act of piety and the hugging and kissing lasted just under an hour. It was dark, it was late, and it was cold. Holyfield looked tired when he left the stage and got in a limousine for the journey back to the Mirage. The first bell was about 46 hours away; Holyfield was getting 20 million dollars and, if he won, the chance to fight Lennox Lewis, who was the WBC champion. The weight of the money and the expectation was lost as he surged under the lights and led his flock in prayers and song. It was beguiling stuff; Holyfield can preach, trust me. On the night they came out in their thousands, and they looked for hope in the words from the heavyweight champion; it was the power of faith and the promise of a hot meal from the kitchens surrounding the praying field. Holyfield was a superstar, his second fight with Tyson had been five months earlier and the whole world had seen the damage Tyson’s teeth had done.

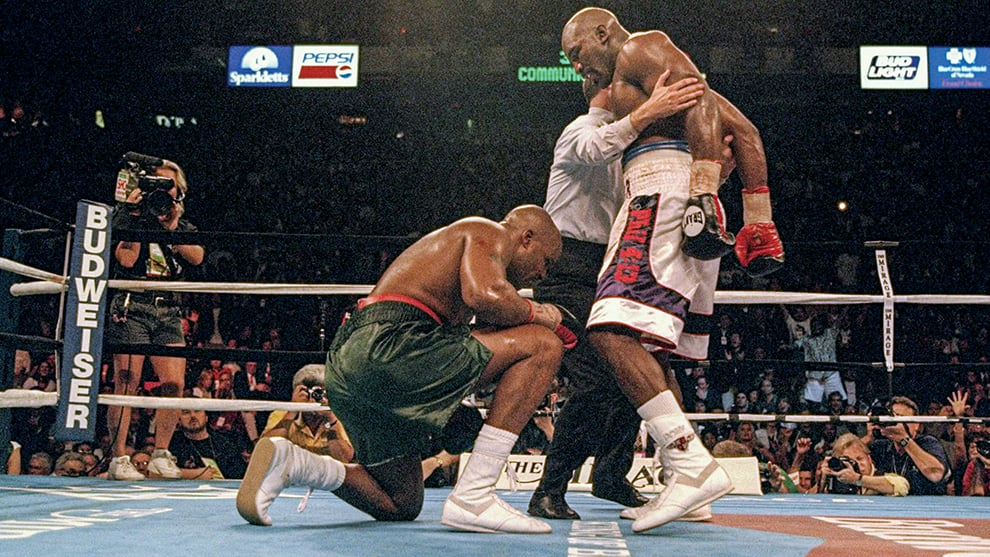

Holyfield stops Moorer (Al Bello /Allsport)

The fight with Moorer finished at the end of the eighth round. Moorer had been sent tumbling five times in total and the referee, Mitch Halpern, had talked to the ringside doctor; it was stopped. Moorer then vanished for three years. Halpern would take his own life a couple of years later. He was a young referee, a kid of 29 when he handled the first Holyfield and Tyson fight. He died of a “self-inflicted gunshot wound.” The extra details surrounding his death are simply too sad.

Holyfield still loves the pulpit. And there is every chance in this circus of veteran scraps that he gets his old dancing boots and gumshield out again. There will certainly be a call and it will not be from the Lord. The difference is that now, he really is an old man, and no dreams or faith can save him.