By Steve Bunce

BEFORE his big fights, Maurice Hope lived with Terry Lawless and his family for a week or two. It was not a Lawless mansion.

Lawless had a couple of teenage children, Sylvie Lawless would cook a big steak on fight day and Hope would listen to ‘classic reggae’ to help kill the time. It has the feel of a Seventies sitcom that I somehow missed.

In Hope’s book, published a few weeks ago, the days and nights of Maurice Hope, British, European and World champion, come to life in a quite exceptional and yet ordinary way. The tiny details make the book, the ‘classic reggae’ albums, the fat steaks. It’s all in the detail; Ron Shillingford wrote the book, and he knows a thing or two about boxing and being a black Londoner in the Seventies and Eighties.

Hope had 14 title fights. He went on the road to some of boxing’s most dangerous outposts and suffered at the hands of the judges; he also pulled off memorable wins a long, long way from home. He fought a series of British title fights, winning the light-middleweight title in just his 12th fight when he beat Larry Paul on the road. It can be hostile in Wolverhampton, make no mistake. Before the first Paul fight, Hope had only fought in public on four occasions; Hope was stuck on private shows, behind closed doors in cigar-friendly hideaways.

In 1975, a sporting club in London was the venue for one of the oddest fights of the Seventies. A fight that still makes no sense, even after reading Hope’s book. Nobody has ever been able to fully explain to me how the vacant British middleweight title fight between Bunny Sterling and Hope, who was the British light-middleweight champion at the time, was staged at the National Sporting Club in the Cafe Royal, near Piccadilly Circus. The simple answer is: they were both black fighters, not ticket sellers and had to accept what was offered.

Hope insists that it was his best payday to that point in his career. Hope believed that Sterling was a ‘club man’, and had been out smoking and drinking. There is an alternative version where the pair clashed at a nightclub. In the title fight, Sterling butted and cut Hope early. The bloody fight finished in the eighth and Sterling was the new champion. Hope had naively believed: “He’s a black man like me; he’s not going to do that.” Sterling got his head in early. Hope lived with Lawless and his family before the fight. It feels like an ancient time and Hope is an expert witness to that time, a man connecting a lost London fight scene to the present. He still shows up at the Repton, where it all started for him. There are very few men like Hope left.

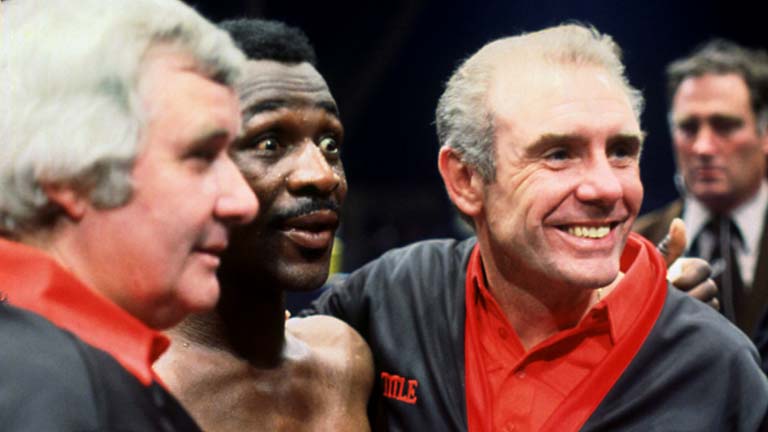

The following year, Hope was in Rome to fight Vito Antoufermo (above) for the European light-middleweight title. It was Hope’s sixth fight of the year. A couple of years later, Antoufermo retained his undisputed world middleweight title against Marvin Hagler in Las Vegas. Trust me, Maurice Hope was a very serious fighter. In Rome, Hope stopped Antoufermo with just 12 seconds of the 15th and last round remaining. Add that to your eternal list of last round wins.

Rome was going smoothly until fight night and then it got ugly. “They were using cement on his face to protect him,” said Hope. It was true. Antoufermo cut often and his people – Maurice just calls them the mafia in the book – were putting the illegal sealant on. Hope tells Lawless: “It’s okay, Terry, I’m going to take his whole head off.” That is bravery and Hope was fearless. The book is raw when it comes to fights. In Rome there was blood and guts before an uppercut finished Vito. Mo was winning the fight, but without the stoppage he would have got a draw and Vito would have retained. The fight was not shown on British television – the Seventies were strange, never let anybody tell you it was a golden age.

Hope’s struggles continued. The next fight was a blatant robbery. Hope met German idol, Eckhard Dagge, in Berlin for the WBC light-middleweight title. At the end of 15 rounds, it was a split draw. Dagge kept his belts, Mighty Mo left Berlin with his bruises. The Boxing News headline: ‘Hometown draw robs Mo’. And Dagge knew, saying to Hope at the end, “Sorry Maurice, but I don’t make the decisions.” Hope was still on the hard road.

Shillingford and Hope deal with the setbacks in style. For every hard night, there is a sweet night out, mostly in Hope’s trusted Toyota driving around the West End. There are a lot of small details that reminded me of so many lost memories. Hope’s role in the signing of Frank Bruno is just one of them.

Anyway, one last fight and Hope is back on the road. Back in Italy. I should add that he also squeezed in another trip to Germany to retain his European title. So, in 1979, Hope stopped Rocky Mattioli to win the WBC light-middleweight title. All the usual barriers were in place – the ref had him losing at the time of the stoppage and the ringside ‘mafia’ were everywhere. Here is Hope on his entrance that night: “Shady figures in the crowd in dark suits and sunglasses were walking around with hands in their breast pockets.” Rocky Marciano was Rocky Mattioli’s godfather! Go on, Mo. You have to cheer as you read. Hope ignored them all and became world champion. It’s just part of the story.

Land of Hope and Glory: The Windrush Kid Who Conquered the World. Maurice Hope with Ron Shillingford.